STRONGWILLED is a multimedia project aimed at helping survivors of religious authoritarian parenting methods recover autonomy and find solidarity, and as reader-supported project, we deeply appreciate those that have joined the community and are funding this work.

TW: corporal punishment, physical abuse of children, sexual abuse.

This post is a transcript of the conversation between Krispin and DL, where Krispin talks about growing up in a small town with conservative parents in Christian ministry and eventually overseas mission work — and what religious authoritarian parenting looked like for Krispin’s childhood, teenage years and early adulthood.

Krispin’s Story

DL: Hello, and welcome to the STRONGWILLED Podcast. I'm D. L. Mayfield.

Krispin: And I'm Krispin Mayfield.

DL: And we are writers, thinkers, and you (Krispin) are a therapist. We also happen to have been married for almost 17 years. We’ve been doing a lot of work around the topic of religious authoritarian parenting methods and helping people heal if they were born in that movement to reclaiming their autonomy.

We just got done putting out two episodes detailing the Religious Authoritarian Parenting movement–including the long term impacts and the family dynamics – to help survivors make sense of their lives. But we also wanted to help people in helping professions and loved ones get some insight into the dynamics of this RAP movement.

Krispin: Yeah, and today we're going to take a more personal tone.

DL: Oh my god, are you ready?

Krispin: I don't know if I'm ready. I mean, we've been doing this podcast for several years now.

DL: Let's try and count.

Krispin: We've been doing it for seven years.

DL: We first started off discussing Adventures in Odyssey episodes, and there are some OG listeners who are probably listening to this now who've been with us since we were crammed into our closet talking about Mr.Whittaker. And now look at us, Krispin!

Krispin: Right. We are in my shed with some acoustic treatment and some professional microphones.

DL: And now we are transitioning into this specific project and honing in on a lot of the underlying history and psychological impacts that influenced the evangelical pop culture movement. So we thought it was a good time to share some of our personal stories. I don't know. Should we frame this as anti testimony?

Krispin: I was thinking about that, it feels like church retreats where you're like “I'm gonna share my story”

DL: I’m your spiritual director, Krispin. I demand you share your testimony.

Krispin: I mean, one of the things about our podcast is that I feel like in a lot of ways we have kept these personal things close to the chest.

DL: Well, we've doled out bits of information. But like anybody who's coming out of an environment that I would say is a totalist environment – so it's an environment that impacts every element of who you are, including like how your brain functions, your developmental stages, your belief about the world, your belief about yourself – basically it’s a high control religion. It takes a long time to unpack it and even develop enough self-awareness about your life, especially if in that environment you have this idea of a testimony, right? You have this idea of how you should be framing your life and sharing about your life. And really quick for people who weren't born into Evangelical Christianity, let’s explain – what is your testimony supposed to be?

Krispin: Testimony is my life was bad, and then I met Jesus, and now my life is good Right, and, and both.

DL: Uh huh. Perfect. You got all the beats, gold star Krispin! So today's not my day for the testimony, it's your day. But I'll just say really quick that there are people like me who were born into it. Um,

Krispin: And who were really good at following the rules.

DL: Who didn't really break the rules, I had to absorb the belief that being a Christian is the only thing that made me happy, that gave me a good life, and that took away my anxiety. Which in the next episode we'll get into that and how that was not true in my case.

Krispin: heh

DL: But it's not my story. Today is Krispin Mayfield’s story. Now before you start Krispin, I'm going to be your hype person for a minute, okay? Krispin Mayfield is truly one of the most incredible people I've ever met in my entire life. And he works so hard and he's so kind and he's so thoughtful. And like many survivors of childhood trauma, he spends his life trying to make life better for people who've also experienced trauma. So that's my big spiel. You're the best. I know it's not fun to talk about some of this stuff, but hopefully we can have a tiny bit of fun even though we might talk about some serious stuff.

Krispin: So going into this I want to just give some trigger warnings for corporal punishment, child abuse, sexual abuse. So just make sure that you're taking care of yourselves.

DL: So I'm so curious, how are you feeling?

Krispin: Yeah. I think there's a lot of that feeling like I'm breaking the rules coming up. And so I think related to like us just doling out little pieces of information over the podcast, there’s such a cultural aspect of like, you don't talk about bad things about your family or family dysfunction publicly. But I think, especially in this environment and growing up in RAP, that to talk about your parents and especially their dysfunction, is to go against the rules, right?

DL: Yeah, I’m glad you named that. So some of us have that feeling that literally comes from our parents, but there's also this cultural expectation if you grow up in Christian circles or high control religious circles, like you're just really shamed for telling the truth of your inner world and your inner experience.

Krispin: Exactly. Which if you've been listening along, you know, is just counter to the whole authoritarian goal, right? Authoritarians are like, yeah, just stick with the program. Don't talk about your individual experience.

DL: But I can't believe I'm saying this, we are not going to be talking about the political and historical parts of the RAP movement okay? In fact, today we're talking about you. So, did you want to give us a really quick snapshot of you and your life and childhood?

Krispin: I was just thinking it would probably be helpful for people to have a timeline of some sort. This is going to be very short, but I was a pastor's kid at one point and I was a missionary kid at one point. I think giving a little bit of framework for that is important. So I grew up for the first 12 years of my life in Roseburg, Oregon, which is a small rural town,

DL: Very conservative.

Krispin: Very conservative, very white. And I'm going to talk a little bit about my dad's career. My dad was a teacher who didn't like students. He was a middle school teacher, but he always said I liked teaching but I don't like students.

DL: He said that?

Krispin: Yes. I feel like him and James Dobson would be best friends. You know why? Because I feel like Dobson is the same. James Dobson spent a lot of time with kids and he did not seem to like kids. Right? And it's really hard to grow up with a dad who does not like kids. Let me just say that. But he did end up quitting teaching because of that, which is good. And then he went into children's ministry. I'm sorry, it didn't occur to me until just now, to be honest. I was like, oh yeah, my dad was a pastor. Wait, what kind of pastor was he? Pastor of children's ministry?

DL: And also, how many children did he have?

Krispin: He had four.

DL: That’s a lot for someone who doesn't like kids, right? Just let me say that.

Krispin: Yeah. And one of those, you know, four under the age of eight sort of things, like every other year.

DL: boom, boom, boom, boom, Yeah. Right.

Krispin: So he was a pastor for a while. I think he really liked that he worked with the Sunday school teachers, but not kids directly. Then when I was 12 we moved to China where he became a principal of an international school. Again, that similar thing not really being around kids that much but he could sort of handle it in small doses. He was, like Dobson, telling other people how to treat kids. Right? So, maybe I'm like, making too much of a parallel here.

DL: I love it. Go for it.

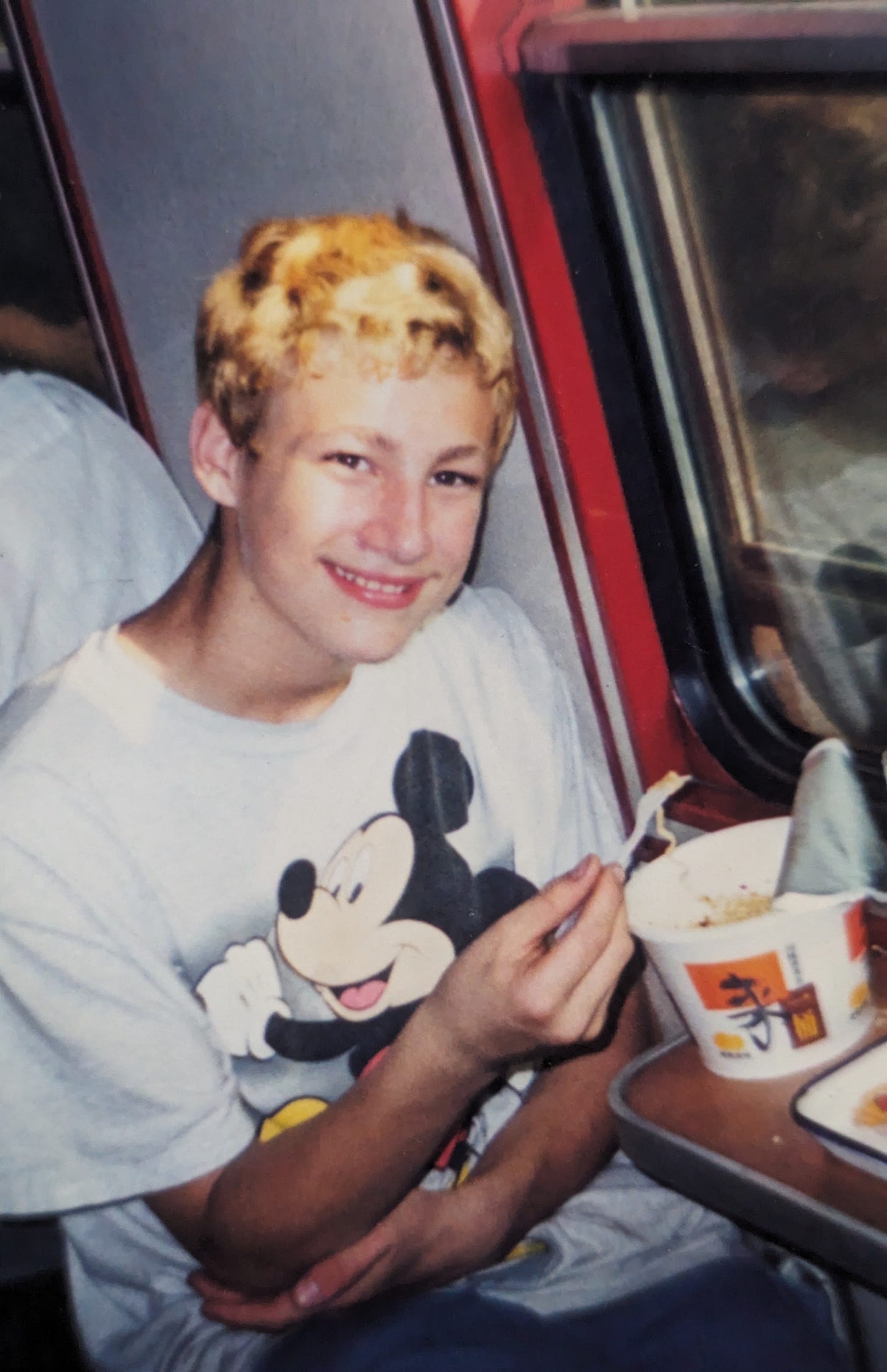

Krispin: So I was there until I was 17. I came back to the States for college. So, me as a missionary kid was me as a teenager mostly. So, I know that missionary kids have different experiences and growing up in another culture from a young age, I would say, is different than being a teenager there.

DL: Can I interrupt? Or do you want me to interject.

Krispin: yeah, interrupt.

DL: So we have a teenager ourselves, and I just think about the impact of uprooting and moving a teenager from the ages of what, 12 to 17? Those are such formative years to be in another culture. That's a big deal. And you probably weren't given any say in that, I'm assuming.

Krispin: No, and I was looking through some old notebooks recently, and in the pre field orientation – which is just sort of like this camp you go to before you go overseas – one of the things that they talked about in this curriculum was how complaining is not good. It literally was telling kids – yes, your whole life is being uprooted, but don’t complain.

I mean I grew up in this rural town of 20,000 people. It was the lumber capital of the US at some point. I moved to a city of 20 million people in China

DL: Where you didn't speak the language.

Krispin: where I didn't speak the language and was just told don't complain. That's what it means to be a good kid.

DL: Damn.

Krispin: Right? So, there's a lot of stuff that has happened between me going to college and now, but I think it's also good to clarify that I'm not a Christian now. So if you're just joining that's something that I left within the last couple of years But I wanted to mention it because as we talk about this piece of growing up Christian I think it's really important to kind of explain a little bit about why it took until I was almost 40 to be able to walk away from the faith.

And I think that will become apparent as I talk through my story. But you wanted to ask a little bit about not even where I started, but like what came before me.

DL: Yeah, it's interesting. Because as we were thinking about us telling our stories, it's hard to do. And we also recognize that we are at a time period where I think more and more people are starting to be open about their experiences growing up in a home that utilized both religion and authoritarian parenting practices.

And so maybe it'd be helpful to just have a few things we think about as we're telling our stories. And one is what led our parents or our caregivers to a more authoritarian and religious way of interacting with the world and utilizing those parenting methods? So thinking about generations and generational trauma, and generational patterns is something that's interesting to me. So I'm just wondering if you have any thoughts on why your parents were drawn to evangelical Christianity and were all in on it.

Krispin: Right. It's interesting because I feel like a lot of people have framed this kind of parenting around this idea that they (the parents) really wanted to obey God. They really wanted to be good Christians. So they read these books and they parented this way. But I don't think that that was true for my family.

DL: I think we need to not make assumptions!

Krispin: Exactly. So I mean, even if we go to a generation prior. My grandpa, my dad's dad, was a superintendent of the school district.

DL: Did he like kids?

Krispin: Uh, I don't think so. I know that when my dad was in high school and he disobeyed his dad, my grandpa punched him in the face. So think about that.

DL: What a good superintendent!

Krispin: I'm not trying to like paint stereotypes, but this was not the backwoods, this is like someone who was like a pillar of the community in Southern Oregon, right? Who was presumably a mandatory reporter, right? Just think about that. My grandpa did not go to church very often, and I'm also going to tell you – he also cheated on my grandma a lot with a lot of people. But I know that on Sundays he was like, I'm so busy. I work so hard. I don't want to go to church.

DL: So he loved the authoritarian part, but not the religious part.

Krispin: Exactly. And even though my dad even went into ministry, I feel that same way with my dad. Like, it didn't feel particularly like he was all in on Christianity. It just was like, he liked the order of it.

DL: And he could be a big man in that world and get respect. The respect due to him.

Krispin: And I think my dad always struggled with having friendships. And so having a church community provided that. I think he got that ministry position because he was volunteering for so long. And so that, you know, kind of explains a lot. I feel like my dad was pretty similar to Dobson in this feeling of like, you know, Kids these days are too rambunctious. They don't listen to you. Blah, blah, blah. That's the problem, right? So that's the legacy of my family. And by legacy, I'm using that in a negative way.

DL: Okay. Can I interject here? Your grandma on your dad's side was super obsessed with religion and you know, we don't have to talk about that, but what about your mom?

Krispin: Yeah, my mom was into the religion. For her it was a way of coping, I think, with anxiety and depression is what I would say. I know that because what she read – which was a lot of the like typical Christian inspirational reading. But also every morning she would blast Steven Curtis Chapman.

DL: Hmmm sounds familiar. Who else in my life blasts music in the mornings?

Krispin: Yeah, right. And I think for my mom it was this idea that life is hard, but how can I feel connected to this divine being that helps me feel better? It felt much more emotional in that way.

Ok so I was thinking we could just start with what it was like, what I was like as a young kid.

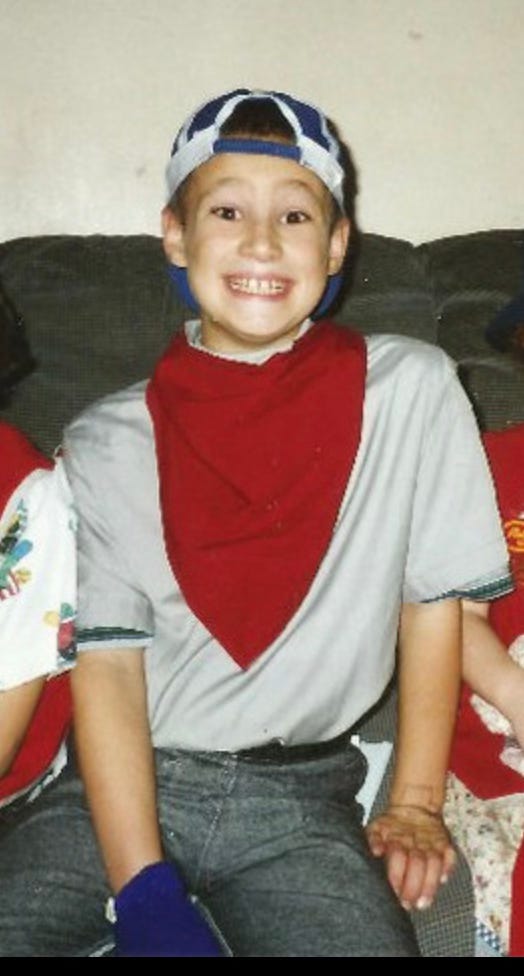

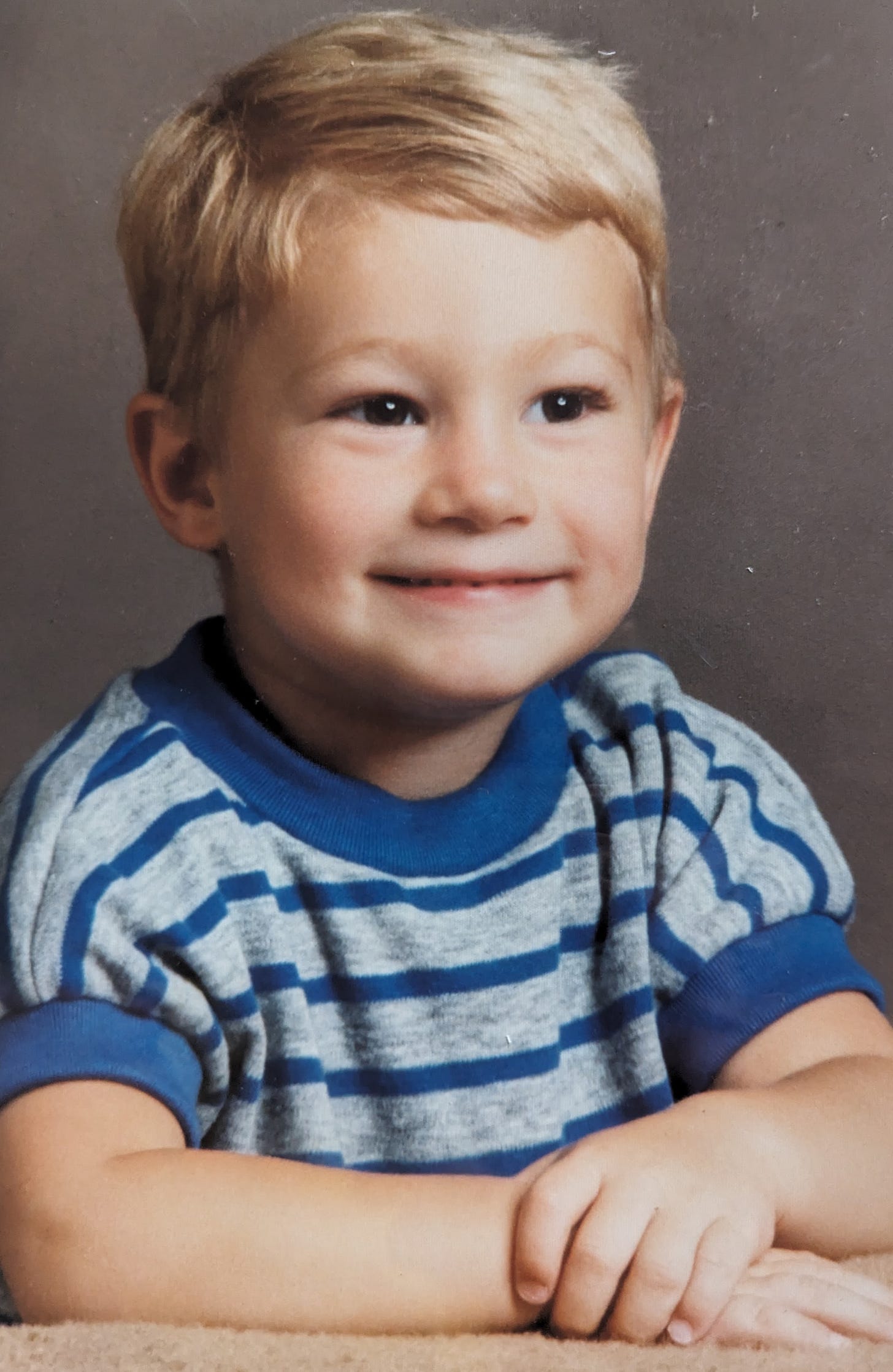

It was hard to remember this. I went back and looked at some pictures, and looked at some stuff from that era. My mom wrote me a letter after my third birthday that kind of described me. And it said that I talked a lot. I had a lot of energy and I was very social and I always wanted to be around other people. And that also that I was a good big brother.

DL: Okay. So that is true. You were the oldest of four.

Krispin: Exactly. And I want to talk about that when we get to elementary school, that role of being a good older brother

DL: Yeah, I think another framework for telling our stories is trying to get in touch with who we were as young children, which of course is hard since we don't always have the cognitive memories, but what were the family stories that you were told about you as a young kid? And then also you in adolescence, since we've talked about these two developmental stages a lot in STRONGWILLED and how they were targeted by these religious authoritarian parenting methods, specifically to squash autonomy in both toddlerhood and adolescence.

So you were very talkative as a little kid and growing up. Were you told that was a good thing or not a good thing?

Krispin: It was funny. My mom in the letter was like, it's sort of hard to keep up with you. But here's something that I do know is that I was not allowed to watch Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles when I was a young kid because I got too excited. I would jump on the furniture and get so excited. And so that tells me that it wasn't like my parents were like, all right, let's try to like figure out how this works. It's just all right, you're not allowed to watch that anymore because you get too excited

DL: Which is sad. You always told this story like it was funny, but it's kind of sad.

Krispin: Right exactly. They're like just PBS for you.

DL: Because PBS didn't excite you. Exactly.

Krispin: I was such an imaginative kid in like fourth or fifth grade. I wrote my own like Encyclopedia of superheroes, but things that I made up, right? So a picture of them on the right hand page, and all of their abilities on the left hand page. I was just always imagining superheroes and that sort of thing. I loved imagining myself as Robin Hood which maybe is why we ended up together.

DL: Oh!

Krispin: A couple of years ago my mom gave me a box of tons of stuff from my childhood. And it was really interesting even looking at like my reading list. And it was like the reading list of what my mom read to me when I was like four years old was like a lot of like Caldecott honors things. And then The Bible tells me so, and all these Bible things. And for me early on being Christian was core to my identity. Right? And that's the way I would say it. Now I'd say being a Christian, but then it was like, I'm Christian. And I did not understand the theology.

But when I was very young, it just was like, I'm a Christian. That is my identity. It didn't even connect to this idea of I've asked Jesus into my heart. That was sort of part of it. But just that our family was Christian. Another story that my mom told me about when I was probably like four or five and we were standing in the grocery store line. Someone behind us had a Bart Simpson shirt. And I turned around and pointed at him and said, we don't watch that show because we're Christian.

DL: God.

Krispin: And it really tells you something about my idea of being a Christian, which the next thing that I took a note on is actually seems contradictory to what I just said. But before public school, it really seemed like everyone was a Christian. Right? Like, even though I might see someone wearing a Bart Simpson shirt, in my mind it was like, that group of people just sort of existed. Because I was in this small town where everybody seemed to be a Christian.

And I was homeschooled until second grade and we only interacted with Christians. The first nine, eight or nine years of my life was where everybody believes this exact same thing. Why would I consider anything else?

DL: I mean, but thinking about Roseburg, most of the people there are Christian. And they could be like your grandpa, your grandparents on the other side, where it's very nominal, but it's also married to white, patriarchal, conservative values, which Roseburg is unfortunately quite famous for.

Krispin: Yeah, one year they like voted to close the library rather than raise taxes.

DL: They made it into the New York times y'all because the people were like, no, we don't want taxes. So the libraries close in Roseburg. Like, which to me is devastating.

Krispin: It’s like Pawnee, Indiana from Parks and Rec level.

DL: Except not funny.

Krispin: yes.

DL: Think about the kids there. Conservatives literally don't want their kids having access to the outside world. That's why they want the library to close. I mean, this is my personal opinion, but it's funny to me to hear you say this, like, I didn't know anybody who wasn’t a Christian until I went to public school in an extremely conservative white Southern Oregon.

Krispin: Yes a lot of teachers went to my church. So there's just all this overlap. Another thing is that when I was a young kid, I was scared a lot. Like I just remember having a lot of anxiety. Um, and also worth noting, I was really cute.

DL: You were a cute kid. I can corroborate that. Adorable.

Krispin: I was this cute kid that was scared of the world and also was like, who am I? I'm Christian.

DL: You were trying really hard to be good and get approval from adults.

Krispin: That was something else that my mom wrote in this letter to me when I was three years old. She was like, it's so cute that you always want to bring your Bible to church too, just like us.

DL: That kind of kid.

Krispin: Right. Exactly. So thinking about second grade and beyond when I'm in this elementary school place and probably even a little bit earlier than that, but I was thinking about what were things that were important to me and I was always afraid of pain. I was afraid of bee stings. I was scared of shots like I had a really had a big space in my head of how long until the next doctor's appointment, that sort of thing. And I was very afraid of being spanked.

And that was something that I don't even remember happening that often. We'll talk later in later episodes about how this works and how a lot of times kids are spanked before they have memories. So there's a lot of like implicit memory there, but I just remember always being aware of like, I could get spanked at any moment

DL: Who did the spanking in your family?

Krispin: I was going to say my dad did the spanking. Yeah, and so it really was like walking on eggshells around my dad all the time. I remember before I'd even processed much at all about my relationship with my dad, I feel like I said something to you casually once, like, Oh yeah, I was happiest when my dad was gone.

DL: Yes, you did tell me that. Right? You were like, my happiest memories from childhood were when my dad was gone.

Krispin: Mm-Hmm. Because he would be gone for like a staff retreat or an elder retreat.

DL: He was a park ranger for a while and went away for long periods of time.

Krispin: Oh yeah.

DL: I remember when I tried to press you on that, you were like, well, he just made us do chores all the time, which is probably part of it. And that's a part of hypervigilance, right? When you grow up with an angry parent that you're walking on eggshells around, it's like, yeah, your dad wanted to put you to work. If you weren't working, he didn't seem to be happy with you. Is that correct?

Krispin: Yes. Totally. And there's always that worry of like, I did the chore and then he gets mad 'cause we didn't do it the right way. I mean I was just thinking about how we had this weeping willow tree that was dying in our front yard so it was always shedding leaves, but the leaves are really small, right? And we just spent all this time raking the leaves and he would go out there and be like, Oh, there's still some on the ground. But they're like so small, right? And that was my whole experience – even if I do the thing that you asked me to do, it's not good enough.

I remember that I really identified with my mom and I really felt a lot of connection to her. But also, she had four kids, and my dad was gone a lot. So, there really wasn't a lot of time for me, I think is the most generous interpretation. I think a lot about my dad and how even my parent’s room was a scary place to me.

I think about our kids and how they come in every morning and they snuggle us and they want to be in our room all the time and be around us. And like, for me, my parent’s room was the place that if I got called in there, I was probably going to get spanked or I was going to get shamed. And that was just something that sort of existed in our house as like this reminder. And I knew that the paddle that my dad went and picked out wood and cut and sanded was there.

DL: Ah! There's something so insidious about that. I'm sorry. Because, back in the day, right? People were like go cut a switch, you know? And they'd go out and get a switch, and people sort of had the decency to feel kind of bad about it. But to to methodically carve and polish and hang it up, and to feel like I'm such a good logical person, because I spank in a logical manner, you know, it's just, to me it's an extra level of insidiousness. And feeling proud about hitting your kids really does come from the Dobson method, he kind of pioneered it.

Krispin: Yeah. And we described this in the last episode, but the whole idea of how you spank your kid, but you are really calm, and you have this connecting moment. You spank them, but then you tell them, I do this because I love you. You know, and you need to hug me. And those are the only times of that sort of level of connection and intimacy with my dad that I remember. Like I don't have any other framework of connection with my dad.

DL: Excuse me while I scream [screams]. Sorry!

Krispin: You don't need to be sorry. My dad did stuff with us, like he would take us on bike rides. Or he would take us on hikes, but that was mostly me complaining, even though I wasn't supposed to, and him getting mad at, me complaining. Or a lot of like, uh, come on Krispin, go faster, go faster, go faster.

DL: Sounds like a fun guy. I can I just interject here? Yes. I remember the first time I met your dad and I was like, I'm a dream boat. Like anyone would be so pleased to have me join their family. Because at this point we were already engaged when I met your dad, because they lived in China and he was back on a visit. And he did not like me and he was the most mild mannered, quiet man and yet he was seething with anger, but nobody could talk about it.

So it was very confusing for me as an autistic person to be like I've never been treated this badly in my whole life. And yet. I'm surrounded by all these other people where it was very normalized. Some of your family members did pull me aside and be like, I'm so sorry Matt was like that.

Krispin: Yeah, yeah, right. No, I'm talking about what it was like to be a kid. And you're like, as an adult, not having grown up with my dad, you are saying this checks out this. There's a consistency here. My parents were really big on “we only spank you if you deliberately disobey us,” which was a big Dobson thing. But I remember one of the times I got spanked was my dad was said don't touch the vacuum. And my friend was there and we got like sort of carried away and I was like pretending like I was a rock star and the vacuum was a guitar.

And I don't remember it being like, Oh, I'm intentionally disobeying. We just were making jokes like kids do, you know? And my dad got really mad and was like, I know that you were having fun, but I have to spank you because you intentionally disobeyed me. So really there wasn't room for like anything. It was such a rigid rule.

DL: Like you couldn’t say, I'm so sorry. I got carried away.

Krispin: Exactly. Right. Yeah. It was this, this assumption of guilt. And in their mind it was like, Oh yeah, we're so graceful as parents because if you make a mistake unintentionally, then we won't punish you for it. But there's no framework of saying hey kids sometimes don't have the skills to obey or they make, they make mistakes by intentionally disobeying or just like understanding that kids are kids.

And I really think that there is this element with my dad was like “I'm very offended that you disobeyed me.” It felt very personal to him. It wasn't about who am I as a kid? What are my needs? That sort of thing.

DL: Well, and that is a part of religious authoritarian parenting methods popularized by Dobson. RAP authors taught parents and they attracted parents who believed that any disobedience was a threat to their authority and was on purpose and must be squashed. And I think that's so sad to train and promote and popularize this idea that your child is intentionally doing this, right?

Krispin: Yeah. And it really comes down to control, right? Like, I need to be able to control you. There’s no room for you for gray areas. Another thing was, and I mentioned this before, but being a good big brother was really significant because for me it really felt like this role I was expected to play.

In some ways, I was like, yeah, I'm a good kid. I'm a good big brother. I internalized some of that. But part of me was like, Oh yeah, there's this part of me that doesn't want to be a good big brother. And that's who I really am, but I need to play this part.

And so I tried to not complain because I didn't want to get spanked. But there's this really poignant feeling that I had for a lot of my elementary years of like, here's who I'm supposed to be -- this good kid that never complains, that always obeys. And that's not who I really am. And so I have to hide who I really am from my parents and from the world and like put on this facade.

It's funny. I was telling you that I thought that I was the teacher's pet and I did such a good job of keeping this mask on. And then I was looking at old grade reports and they were like, Krispin doesn't, like, work as hard as he could and stuff like that. So, but I thought I was pulling it over on everyone. And I think that that is a really big thing that comes up for a lot of people that grew up this way. There is this idea of here's who I'm supposed to be, and that's not who I actually am inside.

DL: And that's what religious authoritarians want. They want someone operating out of internalized shame, never feeling like they're actually good, but working incredibly hard to fit into their assigned role.

And that's so exhausting and you get none of the benefits, truly, right? Because you don't have the internal benefits of viewing yourself as good, as worthy of, respect and self compassion. No, you don't get any of that stuff. And that's so sad! Okay, I'm curious about adolescence.

Krispin: Before we go there for the next couple of minutes I'm going to talk briefly about sexual abuse and the dynamics (not specifics). I was abused by a family member and I remember the sense of “I've done something wrong. I have to keep up this like good face” right? I can't tell my parents about this. And I think that this system really creates kids who are vulnerable to abuse because of that. Because you are told if you do anything bad, you're going to be punished. You're not going to be understood, you're not going to be comforted or listened to and you're just going to be met with punishment.

And I was really scared of my dad, so why would I tell him about this thing that I thought I had done wrong?

DL: Yeah, and how old were you when this abuse started?

Krispin: was 9 years old.

DL: And how long did it last?

Krispin: Till I was 13.

DL: Yeah. And by an older family member, and I think you're exactly right that this system and these ways of parenting create kids who are very vulnerable and easily exploitable, and that shows up in so many ways, and that includes sexual abuse and I really wish this wasn't a common story for people. But it is, and that's part of why we're doing this project, so we're doing it for younger you, you know?

Krispin: I know, I'm crying right now, and I'm surprised by that, because I've processed this a lot, but I just feel really sad for my nine year old self.

DL: Yeah, I do too.

Krispin: So I've been talking about family dynamics with my dad and even abuse within our extended family. But I think it's also important to talk a little bit about what it was like for me going to public school.

I had this idea of “I'm Christian” and that became my whole identity during elementary school. I was bullied a lot, which is also sad. And in my mind, it's because I was a Christian. I had this narrative of like I'm weird and different because I'm a Christian because we, you know, got all this like Christian media that said, you're going to be persecuted, people are going to think you're weird. Which is so funny in a country where Christianity is dominant, right?

But it worked for me to be like, it's because I'm a Christian, not because I did not like fit into gender specific things that people liked. I hated soccer. I hated sports. I just wanted to swing on swings and talk. And I also think I lacked some social skills, but in my mind, it's because I was Christian.

In third grade they said we're not really celebrating Halloween, but on Halloween we'll do a book report. And then you can dress up as a character from your book. So I dressed up as Moses because I did the book of Exodus. And for me, it was a combo of : I'm such a good Christian that I'm reading the book of Exodus. Like I want my teacher, my Sunday school teachers to be proud of me, my Christian teacher to be proud of me, and my parents to be proud of me. And then it also was like, this is a way that I'm witnessing to my class.

And I even found a journal prompt from sixth grade. where I said, I've been known as the Christian kid my whole time at school, but I haven't really had a real relationship with God,

DL: Oh my god,

Krispin: which is so funny. And thinking about that speaks to that disconnect of this face that I'm putting on for the world versus like how I actually feel inside. It's been significant for me to think about how not only did I only know Christians as a child, but then when I was around non-Christians, it was used to actually deeper cemented into my identity. Like the most true thing about me is I am a Christian, right? Which then really makes it hard for you later to be like, do I want to be a Christian when it is synonymous with who you are as a person.

DL: I mean, looking back, does it feel like you had a choice to be a Christian?

Krispin: No, not at all. No.

DL: You were coerced into it in so many ways that it's kind of hard to talk about, but I wanna keep trying! So, can you sum up adolescence?

Krispin: So adolescence was really confusing. My dad really dove into work at that point and wasn't very present. We've had conversations where he is like, I'm really sorry I wasn't present during that time, but in my mind, I was actually really happy that he was checked out.

Thinking through adolescence I moved to China, and I got sucked into this missionary community and I was looking for a sense of identity, purpose, and feeling like a grownup. So I would go to the all-night prayer meetings, even though my parents wouldn't. With the other missionaries they were like, oh my gosh. Look at Krispin. He's so mature. He's coming to pray all night, you know, and getting that validation from adults felt really good. But then there was also a lot of sneaking around and whether it was porn and masturbation or even just stuff like I'm not supposed to have this candy, but my parents are gone so I'm gonna go like eat all the candy.

Which is what which is what happens when you grow up in a home where you can't negotiate, right? And for me it was like you get punished just for asking. like I remember at one point my dad – it was in a particular context of me helping him with something – but he was like, I want you to anticipate my needs!

DL: He’s saying the quiet part out loud to those of us with parents who are like that. Yeah.

Krispin: Yeah. And so it really was this kind of combo of recognizing within myself that there these behaviors that I don't like and that I feel bad about, but I'm still doing them. But also having this Christian identity. I wrote an online magazine where I criticized Christian bands for not being Christian enough. I really built my identity around that. I also had a lot of depression during this. Like I remember a lot of like days of crying all day. In my mind it was like, am I going to be depressed or am I going to do something good for God? I put a lot of pressure on myself and I journaled so much and it just was like writing in circles around things like I know that Christianity is supposed to make me feel these things, feel peace, feel joy. But I don't. What's wrong with me? What am I doing wrong? Or do I need to just accept that even though I've been told that I'm going to feel peace, God is still God, even if I don't feel it.

DL: Okay, can we camp out on this for a minute? Because what's so fascinating is if you grew up in this world, you are kind of told like you should have quiet times and journal and pray. So actually a lot of us do have written proof of what was going through our brains when we were teenagers, and I just wish we could view these as important documents because they are they're important documents of Religious authoritarian parenting and what it does. So I just want to unpack what you said which is so true for a lot of people when they're told this is good news.

I've been told Jesus will help me feel better. I've been told praying, journaling, trying harder, trying to follow God's will, making my entire identity Christian, divorcing myself for my own needs, my own autonomy, my own gender, and sexuality, then I'll feel good. And then you don't.

There might be a few times you feel good. And that happens to all of us in youth group and carefully orchestrated religious events, but then later on you don't feel good. So who do you blame? Do you blame the system? Do you question Christianity? Do you question your parents? No, you blame yourself. And then that cements you even further into trying harder and harder until you break.

And some of us break early, some of us don't break for decades. I'm a late breaker! We're late blooming strong-willed children here at this podcast. And I do think if you have access to journals and stuff, it can be super triggering to read. But I bet you, more than anything, you're going to find some of this circular writing, circular thinking, and just saying the same thing over and over again.

Like, I know this should work. It's not working. What's wrong with me? I should try harder. I'm going to try harder. God, I'm going to try harder. That's what all mine are like.

Krispin: Yeah. And then going into like college, as you know, I was into spoken word for a minute there. And I wrote these spoken word poems being like, why do I fucking go to church every week? Yes, I'm a Christian that says fuck. And then always the end was like, but I know that God loves me. And it really kept me in. Especially if you don't know anyone who's left Christianity.

DL: Well, that's interesting. That is very interesting.

Krispin: I mean, because you and I went to Bible College.

DL: Yeah, of course we didn't know anybody who left. We were with people who were paying thousands of dollars to be even more indoctrinated, you know? So, no, we weren't really around those folks. And you were the edgy person at Bible college.

Krispin: Right. Yes, I was.

DL: The edgy freshman at indoctrination station.

Krispin: Gosh. Yeah. And so I decided during my high school years, that I wanted to be a youth pastor, which was why part of why I went to Multnomah. Would it make sense to start transitioning to talk about late high school, early adulthood and like my parents sort of say in those big life decisions?

DL: I think this is interesting because we've talked about when you were a young child, we’ve talked about adolescence. And now as you're moving into “adulthood”, even though you're still highly indoctrinated, this is a time period where we start to see some strain with your parents. If parents are religious authoritarians they are assuming that they will still have control over you. So you met me when you were freshmen in college. And I think when you met me, it was sort of coincided with you starting to veer a little bit away from your parents and seeing how they responded. So yeah, if you want to talk about that.

Krispin: Yeah, definitely. I mean, so for example, we were looking at a couple of schools and they were both Christian schools, but when it came down to it, my dad was like, this is the school that you should go to.

DL: Because it was cheaper?

Krispin: Because they were like, we think that this will be a better fit for you. So it wasn't really financial. Actually, the other school offered me more aid.

DL: What school was it?

Krispin: The Columbia one across the street.

DL: That one was not great.

Krispin: No, I mean, I'm glad I didn't go there. But it's interesting. It wasn't like, hey, here are our concerns. Let's talk through it. It was just like, all right, here are these two schools. And you're going to go to this one. And that felt pretty normal. And then there's a whole question of even if they had said “well, here's what we think. What do you think?” What I felt like I could have said.

But I actually was thinking a lot about when we got engaged. And you were like, let's do YWAM, which maybe you feel embarrassed about, but I was like, yeah, this is great.

Let’s take a break from school. And my dad was so upset, which is a big part of why he treated you really badly for a multitude of reasons. But one of them was because you were like, let's do YWAM. And my dad was like, no education first. And I think was really upset. He had this feeling he was losing control over me and you were controlling me instead.

DL: Which is funny, I mean, there is that dynamic at play. I never dated before you, and I do remember when we first started dating. I was sort of like, Oh my God, this guy is going to let me walk all over him. Like you were begging to be ...

Krispin: Dominated. Dominated! Ha.

DL: I wasn't gonna say it! But yeah, I was like, I don't know if I want to be a dom, you know, like maybe I want more than just that. Because I can slip into that role quite easily, thank you very much. But it was very interesting to see your dad and be like, Oh, Krispin is very used to not making decisions for himself. And it was me and your dad battling it out, which wasn’t the reality at all. I was just brainstorming. How can we serve God?

Krispin: Right, exactly, and you assumed like, he's a missionary. He'll be excited that we want to do some short-term missions work.

DL: And it's not about education because Multnomah Bible College was a horrible education. And I feel fine saying that it is all indoctrination materials masquerading as higher education. So I'm like, That's not what was happening at Multnomah, anyways. And you weren't very into the curriculum, if I can be honest.

Krispin: I was not. I was, my head was somewhere else. I do not remember much of anything from Bible college, but yeah, that was a lot of what it looked like. I would say the first 10 years of our marriage, things would come up where my dad would be like, hey, like we're coming to stay with you for a week. And me being like, well, let me talk to D.L. about it and see if that's going to work. And him just being like, how could you say no to me? Right.

DL: I remember when we went to China for two months to hang out with your family. And I could see, you know, all that of that. And your dad super hated me and would try and get you away from me to have a conversation with you because he didn't want me there.

Because I think he was really unused to people calling him on his bullshit. And I was pretty nice about it, but I was like, wait, what? What are you saying? And so it was just very interesting as that continued on in our marriage, I knew your family blamed me for a lot of stuff when in reality, it was you, you were the one standing up to them, not me. But they were like, Oh, let's just blame Danielle, which I was like, Oh my God, you obviously don't know Krispin. Yes, you're kind, but if you back Krispin into a corner, y'all, you get bit.

Krispin: So I'm going to talk about sexual abuse for a minute and trying to work that out as an adult. So when I was in my early 20s, I was like, oh, that was sexual abuse. I thought that it was me being a bad kid but then I realized oh, that was sexual abuse.

I was trying to figure out what to do, so I went to therapy a little bit, I talked to a couple of therapists and they were like, yeah, just talk it out with your family. And so that was me being like, hey, we need to address this. Like this person (my abuser) could still be a danger to kids now. But it was in this framework of I have to go to the elders of the family, which is my dad and my uncle and see what they say.

And they basically were like, well, why can't you just get over this? Why are you making such a big deal out of it? Probably some of that is like, why is your wife making a big deal out of this? Like some of that narrative. So basically, they were like, yeah, this isn't something that we really want to address.

And I was just like, okay, you're the older, wiser people and I listened to them. And it took a little bit of time to figure out like, oh, actually this is just a dysfunctional family system. That's trying to cover up abuse in the family.

DL: Yeah, totally.

Krispin: Thinking about stuff like that, like, I mean, people know about that happening in churches, but it also happens in families.

DL: Oh, so many families

Krispin: And there is this idea of the parents being older, wiser, and they’re Christians, right? I was 24 years old, which is not an old adult, but I'm not 18. And I think an 18 year old should also be able to say, Hey, let's talk about abuse. But like thinking about me being 24 with a child of my own and then acting in this way as though like I'm a kid and I need your permission to take action on this.

DL: Again, is a hallmark of religious authoritarianism. You have to comply to the authority in your life, even if you're an adult. Right? And you tried so hard to do that because you knew how much pushback you would get if you just went off on your own and were like, I'm going to be honest about the abuse. I'm going to make sure this abuser is not able to work with kids because they were, and you know, doing stuff like that..

Krispin: And then the self doubt that would come up. I can feel in my gut that I'm doing something wrong by going against my dad, you know? And so yeah. And I think that's really significant, that's obviously a pretty intense topic, but I think that shows up for a lot of people in a lot of different topics. Like if I'm not doing what they want me to do, then I'm doing something wrong.

DL: You have to listen to the elders, the patriarchs. So you made your case, you asked them to do something and they said, okay, well, if this person works with kids, then we'll do something. Well, they didn't.

Krispin: Yeah. They also said well, look at Matthew which says you need to directly confront this person before you talk to anybody else.

DL: Yeah, confront your abuser. That’s what God wants you to do. Over and over and over again. Yeah, I just think this kind of stuff is happening in so many families and people use religion as a cover for continuing dysfunction. And at what point are we just going to be able to say any system, a family system, a church system that abuses children needs to be exposed? Every single one of them needs to be exposed. And the more it's perpetuated in families, right, the more we allow it to perpetuate in these institutions. So, whew, we had to go through a lot of that. So that was a lot of your early 20s, is was about breaking free of that control.

Krispin: Yeah, I think it's also worth mentioning that I eventually set some strict boundaries with my parents that led to estrangement. And we'll talk about that in a later episode. So, as I've talked so much about my relationship with my parents, my parents are not in my life right now. And going through that process and making sense of all of those dynamics in adulthood is something that we're going to be talking about this fall, which I'm excited about.

I'm very passionate about empowering people to set those boundaries with their parents because it creates such a toxic dynamic when you grow up if you aren’t allowed to do that.

DL: And this is what often happens right? These RAP parenting methods, these ideologies, living your life as an authoritarian has consequences, right? The second a person (your child) starts to actually be like, I'm my own person, can you respect that or not? Religious authoritarians can't respect that, most often.

Krispin: And it often feels very personal to them.

DL: Yeah. And so they're quite happy with the estrangement in a way, because they're not able to see you as your own person.

Krispin: I think that there are a lot of different parental responses. But I do think that a lot of times they will have their own narrative that helps them feel better about themselves and upholds their authoritarian framework.

DL: Can I ask one question? Because I know we have to wrap this up, even though there's so much we didn't talk about. How do you think becoming a parent has impacted you when it comes to like reassessing your childhood and how you were raised and some of these methods?

Krispin: I think about growing up with this feeling of like, you're falling short, you're not doing what you should do, you should be better. And then seeing my kids grow up with, you know, all their like propensity to like not obey and not be calm and whatever like kids do.

DL: Wait, kids are supposed to be calm and obedient?

Krispin: Exactly right. And, feeling my delight in them being kids really helps me reparent myself. Oh, there wasn't something wrong with you. There wasn't something wrong with you that you wanted to like jump on the couch when Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles came on or when you complained about how hard it was to keep up with your dad on bike rides. That doesn't mean that you are inherently flawed as a person! I feel like we just decided off the bat that we weren't going to spank our kids.

This project has really prompted me to think more about what was it like to be spanked as a kid. I just think about how on a very baseline level of how I view my kids and not seeing them as like inherently broken is important to me. The religious authoritarian parenting framework does so that. It says kids are evil. I mean, they won't say that, although sometimes they say evil. Sometimes they say evil. They have their own will. They are disobedient. They are malicious, manipulative.

DL: And basically will turn into dictator tyrants unless you control them, and they learn how to be controlled.

Krispin: Exactly. So, I think recognizing oh, that was the philosophy that undergirded my dad's interactions with me especially. And that really shaped how I viewed myself as a person. Because that's how humans work, is that we view ourselves according to the feedback we get from others.

DL: Yeah. And okay. Last question, if that's okay. How are you doing with that sense of self these days? Because the truth is, just because you start processing this doesn't mean all of a sudden you have the skill set of having self-compassion. I think that's probably the biggest takeaway I've gotten through all my research and therapy and personal experience in parenting my own kids. You can't just snap your fingers and like, Oh, I now view myself with gentleness and self-compassion. And I know that I was not born sinful and evil, but I'm just a human in a world, you know, like, how are you doing with that?

That sort of self-talk, self-perception, self-compassion?

Krispin: For me I really grew up very hypervigilant and this feeling of like I'm always being seen by someone else in a negative way.

So for me, taking time alone, which sometimes is hard with work and having kids and stuff, but really connecting with myself, and things that I like, then allows me to show up in my relationships and be like, I know who I am. I like myself, and I'm not coming to this from a place of “you're judging me or assessing me” way like I used to.

DL: I love this and let's truly end this on a high note and tell me, well, I already know, but tell the listeners, what are some things that you're really into that you're like, wow, this is me. It could be related to childhood or adolescence, or it could just be something that is sort of new.

Krispin: Yeah, a huge thing that we didn't even have time to talk about here was that I've always been fairly genderqueer. And so that was a big point of strain, I think, between my dad and I. My dad who was a football coach and who was always disappointed that I didn't want to do sports ball. So yeah I’ve been leaning into more femme things like painting my nails and stuff.

The other thing that I think about is just listening to music in our bonus room and just being myself and enjoying that. I make music, I do photography, but just that idea of sitting and being like, Oh, I noticed l like the way that the music impacts me. It just feels so good and significant and another thing that I was told all the time growing up was like you're too sensitive. So just leaning into that like yeah, I am sensitive and I love that about myself.

DL: It’s hard to share about our childhoods! It's really not easy if you grew up in these kinds of environments. There are so many barriers, psychological, cultural and even physical, right? I do not think you feel good right now, probably, and you know a lot of tools to ground yourself, to take care of yourself. You're a therapist, you've been doing this work, but it's still not easy. And we do this out of a sense of solidarity and knowing that we are by far not the only people who grew up this way and are processing it later in life.

So we just hope those people who are listening that you can start to think about your own story and think about ways you might want to share it.

And then also think about ways to connect to yourself. Just like Krispin described – I just think it's really cool to see how you've embraced music and being a little weirdo! I think that's really great!

Krispin: I mean you're such a cheerleader to me and just always encouraging me to do those things and to stop trying to care for everybody else all the time. So I really appreciate it.

DL: You are not an authoritarian's dream. Instead you're just weird Krispin and I love you. So thanks so much for listening. Anything else to add, Krispin?

Krispin: I just want to say thanks so much for y'all listening to my story and I do hope that it's helpful. I know that everyone's story is different but I do hope that it gives you a point to think about like, yeah, what was I like as in these different ages and what did I need and what did I get? I think that's such a good framework.

DL: Yeah, next up – It's me. People are not ready!

Krispin: but we will be back soon with D.L.’S story of growing up in this sort of setting and I'm really excited to hear about it and to dig into that. So we will be back soon. Thanks, everybody!

Whether you are someone who was raised with RAP methods, a therapist who works with religious trauma clients, or somebody who is simply interested in these topics, we hope you found this resource to be helpful. STRONGWILLED is a reader-supported publication and we are so grateful for all of the support we have received — there are over 2,000 of you here! You can help this project continue on by liking, sharing, and subscribing to the Substack and by supporting us financially.

Who we are:

D.L. Mayfield (they/them), is an autistic non-binary writer and parent. D.L. grew up as a homeschooled evangelical pastor’s kid, and spent many years in the Christian writing world before deconverting from Christianity in 2022, and they enjoy deep diving history in order to find patterns.

Krispin Mayfield (he/him), is a licensed therapist and author who specializes in religious trauma and neurodivergence. Krispin was also raised evangelical and spent his teenage years as a missionary kid before also leaving Christianity in adulthood. Krispin and D.L. have been married for almost 17 years and are the parents of two incredible children.

Share this post