Do you appreciate the work and scholarship of STRONGWILLED? Consider supporting this survivor-centric and survivor-led project — either by subscribing, sharing this project with others, or supporting us financially. As always, STRONGWILLED offers free paid subscriptions to members of the LGBTQIA+ community, thanks to the generosity of others (simply email us at strongwilledproject at gmail and let us know you need the scholarship). When you support this project with a paid subscription, you are allowing us to offer up that gift to others.

Chapter 10: Spare the Rod, Spoil the Child : The State of Corporal Punishment in the U.S.

TW/CW: references to corporal punishment, physical abuse, sexual abuse.

“When a child hits a child, we call it aggression.

When a child hits an adult, we call it hostility.

When an adult hits an adult, we call it assault.

When an adult hits a child, we call it discipline.”

-Haim Ginott1

In 1989, the UN created a resolution about the rights of children, which included the statement that children should be free of “physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s).’ Every participating country ratified the resolution except one: the United States of America2. To date, corporal punishment (the use of physical force with the intention of causing a child to experience pain so as to correct their misbehavior)3 is still permissible for parents in every state in America. Corporal punishment (using paddles), is allowed in public schools in 17 states, and is legally allowed in private schools (many of which are religious) in 45 states4.

In 2024, children in the U.S. continue to be unprotected by their governments, communities, and parents against the threat of physical violence5. While corporal punishment, both at school and in homes, remains a hotly debated issue, the evidence of its harm is not. Through recent studies, as well as meta-analysis compiling decades of research, researchers have found that spanking has been associated with:

anxiety6

depression7

lower interpersonal skills8

suicidality9

low self-esteem10

substance use problems11

increased risk of experiencing physical abuse later in life12

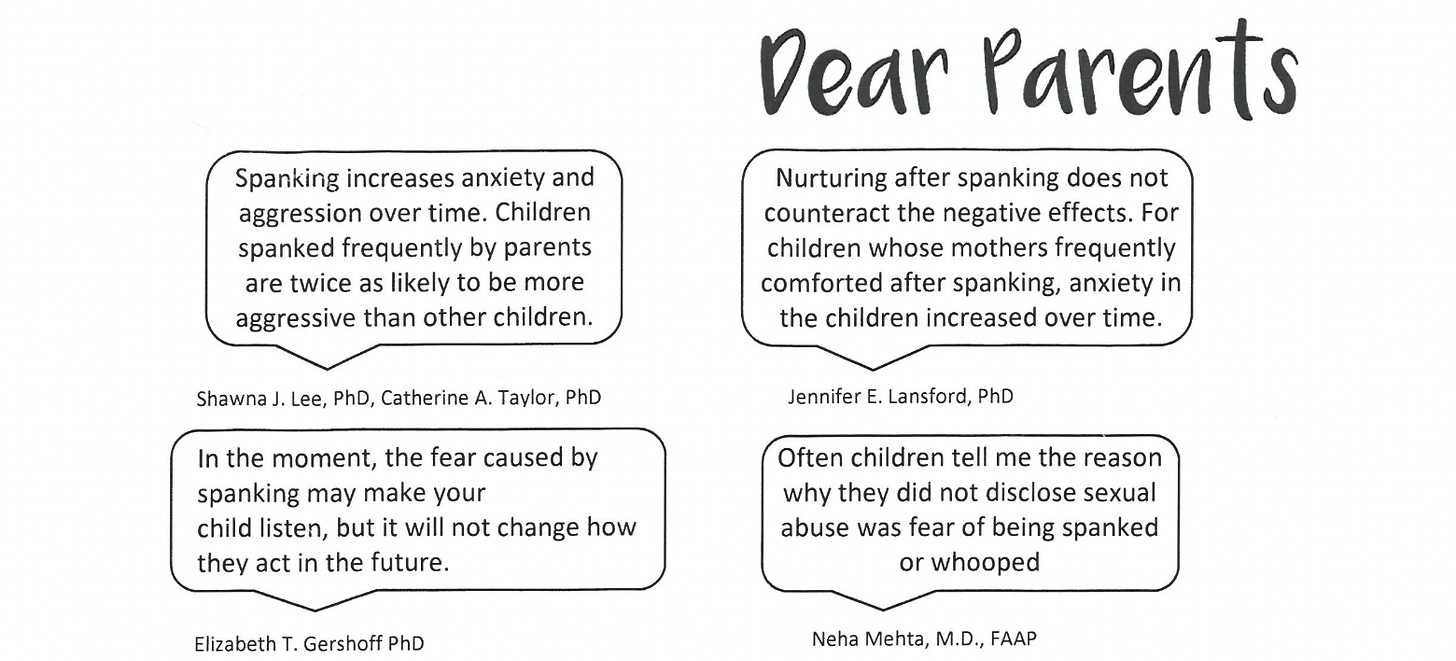

Here is a snapshot of what research has shown us about the impacts of spanking on children in a visual form:

These are images from the Kansas chapter of the American Association of Pediatrics (you can access the full handout, with scientific studies and references here).

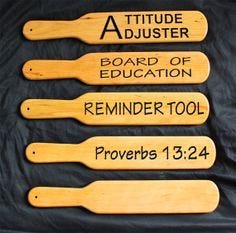

Despite clear evidence that it’s harmful, religious authoritarian leaders have fought hard to shape and maintain the US’s cultural and political stance on spanking. In the typical religious conservative playbook that dismisses research and claims the basis of their position in the Bible (see also: policies in the US for the rights of LGBTQIA+ people), leaders like Billy Graham13, James Dobson, Ted Tripp, and Gary Ezzo claim the Bible and what they coined “Judeo-Christian ethics” as the basis of their authoritarian parenting philosophies instead of research.

It’s hard to imagine that James Dobson, who holds a doctorate in psychology from the The University of Southern California, and popularized corporal punishment for evangelicals starting in 1970 with his first (and best-selling) book Dare to Discipline, wasn’t aware of the research that was beginning to prove the harmful impacts of spanking on children even in the 1960s. Partly because he explicitly taught his readers to distrust experts who were outside the Christian fold time and time again: “I don’t believe the scientific community is the best source of information on proper parenting techniques,” he wrote in Dare to Discipline, and he has stuck by this sentiment14. In nearly all of his books, he claimed to use the Bible as his source for whether or not spanking is harmful or helpful instead of research. This would be a trend with nearly all religious authoritarian parenting experts, who not only dismissed the scientific research, but who also claimed that there was no evidence that spanking in a calm and rational manner was harmful or had long-term impacts on children.

Appealing to an ancient text to convince parents that “spare the rod and spoil the child” is godly wisdom, sowing distrust of the scientific community, and linking corporal punishment to a religious ritual has resulted in the United States being far behind the rest of the world when it comes to identifying and protecting the rights of children.

In books and on his popular Focus on the Family radio programs, James Dobson has regularly galvanized his audience to oppose any policies that could protect children from corporal punishment, framing the issue as government overreach (an easy rationale to make to his largely republican audience). He tells his audience, “there are many ‘children's-rights advocates’ in the Western world who will not rest until they have obtained the legal right to tell parents how to raise their children.15” He refers to countries like Sweden and Canada that have taken steps toward protecting children from corporal punishment, stoking fears that similar policies could be enacted in the US. Others like John Piper, John MacArthur and more have all done the same thing, equating child’s rights activism with being persecuted for living out the Christian.

Unfortunately, as long as Christianity and an patriarchal authoritarian view of the Bible are used to shift the conversation away from the research, it will continue to be an uphill battle for American society to face the actual devastating impact spanking has on so many kids, and take action to protect them. Perhaps the best way to begin is to start by looking at what RAP authors would most want us to ignore: what does the research say about the impact of corporal punishment — regardless of whether or not it is done in anger or as “discipline” — do to children

Spanking Changes the Brain

While researchers have been indicating for decades that spanking tends to be both harmful and ineffective, in recent years, they’ve been exploring how traumatic it is, and how it changes the brain. George Holden is a researcher who listened to audio recordings of parents and their children interacting, tracking what corporal punishment looks like in real life16. He said, “It was clear from the tapes that these children were experiencing trauma...If it happens enough, it can result in neurological changes in the brain caused by stress hormones.”17

One study by researcher Jorge Cuartas and his co-authors found that spanking undermines feelings of safety, and promotes hypervigilance. They found that children who were spanked were more attuned to potential threats, and which even included neutral faces18. In other words, these children were more likely to be constantly monitoring the facial expressions of others, feeling on edge, and easily thrown into dysregulation if someone else seemed unhappy — even if it was simply the absence of a happy facial expression. One of the authors of the study compared it to the impact of sexual abuse, showing a change in how the brain processes the world, undermining and eroding a sense of safety: “You see the same reactions in the brain…Those consequences potentially affect the brain in areas often engaged in emotional regulation and threat detection, so that children can respond quickly to threats in the environment.”19

There’s also evidence that spanking impacts brain development. One study found that kindergarteners who were spanked had lower self-control, while other studies showed lower inhibition and lower cognitive flexibility.20 This means that kids had more difficulty pausing before a behavior and thinking about their actions, and more difficulty transitioning between tasks21. These are all aspects that reflect executive functioning of the brain, and hinder the child’s ability to respond in ways that parents ultimately desire.

Evidence has shown spanking to be connected to how we relate to success and failure even in adulthood. One study found that kids that were spanked in childhood, by adolescence showed an increased reaction in the brain when errors were made22. The same study found that in these same adolescents who were spanked in childhood, their brains didn’t respond as strongly to success. This means that you’re more upset when you make an error, making it harder to deal with failure, or simply making a mistake — but when you do it correctly, you don’t get the same good feelings that others do.

We commonly see these outcomes in perople with Complex PTSD, including chronic hopelessness (“I’m always going to mess things up”), shame (“there’s something wrong with me”,) as well as difficulty appreciating when you are successful and life is going smoothly. The study seems to indicate that due to spanking, the brain becomes preoccupied on making mistakes at the expense of appreciating when things go well. It would make sense that this could create some patterns of thinking that focus on what goes wrong, but difficulty focusing on what goes well — setting people up for mental health challenges.

There’s No Such Thing as “Appropriate Spanking”

While advocates of Christian spanking claim that spanking is only harmful when combined with other types of maltreatment (verbal abuse, hitting in other contexts), or when it’s done in anger, the research shows otherwise.

For example, Tedd Tripp, author of the best-selling books Shephearding a Child’s Heart, routinely claims that in his methods he advocates spanking that is only harmful when done in anger and that no research has studied his type of spanking. This is untrue, and in a meta-analysis from 2016 on 75 studies representing 160,927 children, the authors write: “Our first research question was whether spanking would [still] be associated with detrimental child outcomes when studies relying on harsh and potentially abusive methods were removed. The answer to this question is: Yes, it is.”23

In recent years, researchers have taken into account both negative and positive factors surrounding spanking. They’ve studied the impact of spanking when other types of abuse24 or adversity (like poverty)25 are accounted for. It’s still harmful. And they’ve also considered what happens when spanking is done in the context of a warm26, secure parent-child relationship27, and they still find that it’s harmful. Researchers Janique Fortier, et al., believe that our society (including the academic world) has done a disservice to the conversation by “using language such as “appropriate” versus “inappropriate,” “abusive” versus “nonabusive,” “reasonable” versus “unreasonable” physical punishment.” They write, “These perceptions persist despite empirical evidence confirming that spanking is an adverse childhood experience (ACE).”28

In an article in TIME Magazine, researcher Elizabeth Thompson Gershoff said, “Most people think child abuse happens because the parent is psychotic and hates the child, but tragically, it happens when people who think they’re doing the right thing hit a kid too long and too hard, sometimes with an object.29” In a Canadian study that analyzed confirmed abuse found that in 75% of cases, the abuse was perpetuated as discipline30. Despite the narratives that there’s abusive physical punishment and non-abusive “discipline”, evidence shows that parents who believe they are using reasonable corporal punishment often do not have an accurate view of their actions, causing harm and trauma for their children.

Why it Works for Authoritarianism

Lastly, we can see how spanking aids authoritarian goals because it’s been associated with lowered internal morals31. In other words, spanking encourages kids to follow the rules immediately and without objecting outwardly, but discourages them from developing an internal compass of right and wrong. It sets kids up to dismiss their own sense of right and wrong in favor of listening to and obeying and outside authority, which is the ultimate goal of both authoritarian politics and high control religions. Dr. Dobson, and other religious authoritarian parenting experts, have long been vocal about how their methods create compliant children and law-abiding citizens. But in order to promote their methods, they hid their political aims under the guise of religion — and were so successful that for many evangelicals, using corporal punishment on children to discipline became synonymous with whether or not you were living out your Christian faith.

For children raised in these homes, the impacts of spanking were not only minimized, but erased from the narrative. Children were taught to thank their parents for the corporal punishment, and to build trauma bonds with their caregiver after experiencing physical pain. The long-term impacts of this “gentler” form of corporal punishment are difficult to summarize, but the gaslighting that children received in these moments of punishment often ensures that the child never grows up to recognize what they experienced as abuse. If a child grows up believing this is the most loving thing a parent can do to a child, the chances are that they will replicate this pattern with their own kids, creating a system of control and a cycle of generational trauma that masquerades as Christian love.

In later chapters, we will look at some famous authoritarians in history and their relationship to corporal punishment — as well as delve into the systemic issues that normalize violence against children and what that means for society.

For today, we wanted to give a clear picture and a meta-analysis of the information on spanking and its impacts on children — regardless if it is done in a ritualized religious manner or not.

If you find this content helpful, please consider sharing this post with people you feel it might resonate with.

For our paid subscriber community, please let us know in the comments (if you choose) about how the research informs your personal experience with corporal punishment in childhood. Does it resonate? Validate?

McGregor, J., McGregor, T. (2017). Coping with Aggressive Behaviour. United Kingdom: John Murray Press

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convention_on_the_Rights_of_the_Child

Definition of corporal punishment from here: Straus, M., & Donnelly, D. (2017). Beating the devil out of them: Corporal punishment in American children. Routledge

“In schools, a teacher or administrator typically administers corporal punishment by using a large wooden board or “paddle” to strike the buttocks of a child. A typical state definition of school corporal punishment is the one offered in the Texas Education Code, which specifies permissible corporal punishment as, “…the deliberate infliction of physical pain by hitting, paddling, spanking, slapping, or any other physical force used as a means of discipline.” Gershoff : Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public Schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy.

In researching this topic, we came across some devastating headlines, perhaps most disturbing to read was a local news story in Oklahoma: “Oklahoma lawmakers weigh corporal punishment on special needs students,” As we near the end of the year 2024, parts of our country are wrestling over whether it’s appropriate for teachers to hit kids who have disabilities, or not.

Anderson, J. (2021, April 13). The effect of spanking on the brain. Harvard Graduate School of Education. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/21/04/effect-spanking-brain

Anderson, J. (2021, April 13). The effect of spanking on the brain. Harvard Graduate School of Education. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/21/04/effect-spanking-brain

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0145213422003519

Gershoff, E, et al. Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse & Neglect, Volume 71, 2017, Pages 24-31

Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. J Fam Psychol. 2016 Jun 30(4):453-69.

Gershoff, E, et al. Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse & Neglect, Volume 71, 2017, Pages 24-31.

Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. J Fam Psychol. 2016 Jun;30(4):453-69.

Dobson, J. C. (2014). The New Dare to Discipline. United States: Tyndale House Publishers. P. 16

https://dobsonlibrary.com/resource/article/9e6c1b33-b341-4617-aa11-70c9744fdf11

In this study, Holden found that corporal punishment was used much more frequently than what is typically reported. While previous measures found that parents report using corporal punishment on their two-year-olds 18 times a year, his findings indicated it was closer to 18 times a week.

Foley, D. (2015, April 14). The Discipline Wars. TIME.com. Retrieved September 15, 2024, from https://time.com/the-discipline-wars-2/

Anderson, J. (2021, April 13). The effect of spanking on the brain. Harvard Graduate School of Education. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/21/04/effect-spanking-brain

Anderson, J. (2021, April 13). The effect of spanking on the brain. Harvard Graduate School of Education. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/21/04/effect-spanking-brain

Jeehye Kang, Spanking and children's social competence: Evidence from a US kindergarten cohort study, Child Abuse & Neglect, Volume 132, 2022,

Jeehye Kang, Christina M. Rodriguez, Spanking and executive functioning in US children: A longitudinal analysis on a matched sample, Child Abuse & Neglect. Volume 146, 2023,

Kreshnik, et al.Corporal Punishment Is Uniquely Associated With a Greater Neural Response to Errors and Blunted Neural Response to Rewards in Adolescence. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, Volume 8, Issue 2, 2023,

Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. J Fam Psychol. 2016 Jun;30(4):453-69

Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. J Fam Psychol. 2016 Jun;30(4):453-69.

Lee SJ, Pace GT, Ward KP, Grogan-Kaylor A, Ma J. Household economic hardship as a moderator of the associations between maternal spanking and child externalizing behavior problems. Child Abuse Negl. 2020 Sep;107:104573

Jeehye Kang, Christina M. Rodriguez, Spanking and executive functioning in US children: A longitudinal analysis on a matched sample, Child Abuse & Neglect, Volume 146, 2023

Kaitlin P. Ward, Shawna J. Lee, Garrett T. Pace, Andrew Grogan-Kaylor, Julie Ma, Attachment Style and the Association of Spanking and Child Externalizing Behavior, Academic Pediatrics, Volume 20, Issue 4, 2020, Pages 501-507

Fortier J, Stewart-Tufescu A, Salmon S, MacMillan HL, Gonzalez A, Kimber M, Duncan L, Taillieu T, Davila IG, Struck S, Afifi TO. Associations between Lifetime Spanking/Slapping and Adolescent Physical and Mental Health and Behavioral Outcomes. Can J Psychiatry. 2022 Apr;67(4):280-288

Foley, D. (2015, April 14). The Discipline Wars. TIME.com. Retrieved September 15, 2024, from https://time.com/the-discipline-wars-2/

Durrant, J, Ensom R. Sept 2012. Physical punishment of children: lessons from 20 years of Research CMAJ. 2012 Sep 4;184(12)

Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. J Fam Psychol. 2016 Jun;30(4):453-69

This made me stop — “They found that children who were spanked were more attuned to potential threats, and which even included neutral faces. In other words, these children were more likely to be constantly monitoring the facial expressions of others, feeling on edge, and easily thrown into dysregulation if someone else seemed unhappy — even if it was simply the absence of a happy facial expression.”

Wow, that clicks. I have noticed that it is very, very hard for me to see anyone, especially my kids, unhappy. It seems more than just a motherly instinct.

And the smiling, happy people countenance — could that be a result of this hypervigilance for some people?

The principal of my private K-8 Christian school had a paddle hanging in his office. My parents used to spank us on our bare bottoms by hand, but my mom switched to "the wooden spoon" after she hurt her palm by hitting too hard. (She also joked about upgrading to a spoon with a thicker, unbreakable handle.) Gee, I wonder where my constant subconscious fear of "getting in trouble" comes from, not to mention my innate fear and distrust of all "authority figures"...