A daughter of Focus on the Family speaks out

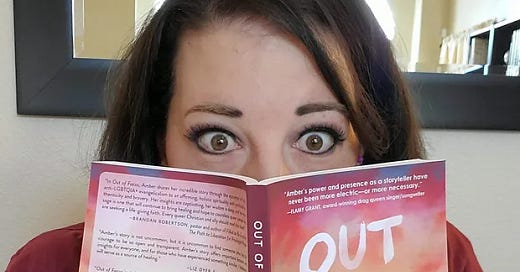

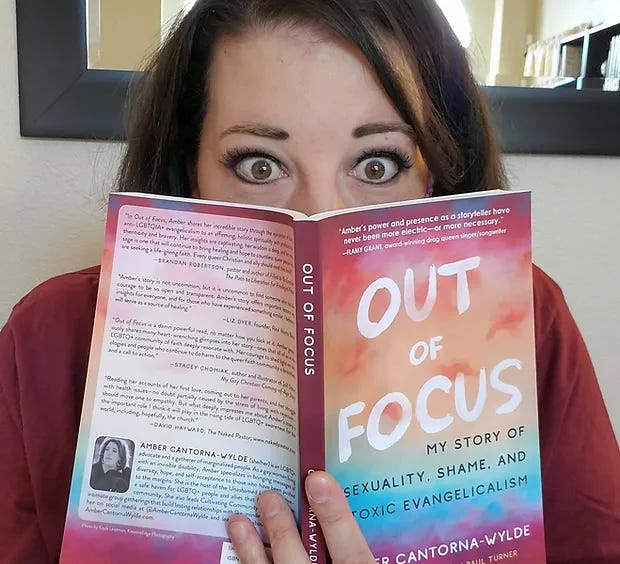

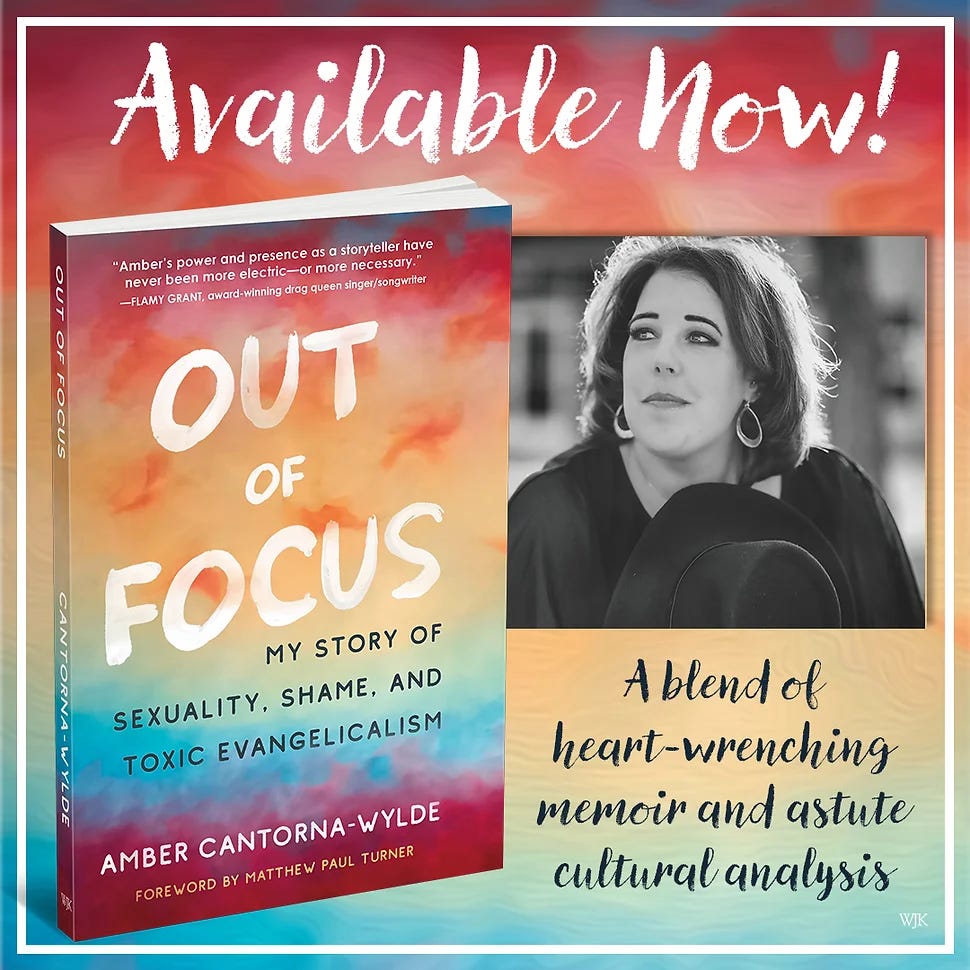

An interview with Amber Cantorna-Wylde, author of the memoir Out of Focus: My story of Sexuality, Shame, and Toxic Evangelicalism

“When you're forced with a decision to be authentic to yourself or suppress who you are — and you are facing the mental health ramifications of that — it doesn't really become a choice anymore.“—Amber Cantorna-Wylde

Welcome to STRONGWILLED, a multimedia project aimed at helping survivors of religious authoritarian parenting build autonomy and find community. We are so glad you are here! Today we have a special interview that has been edited and condensed for clarity. You can listen to the audio version of this interview here.

STRONGWILLED is a reader-supported publication. Please like, share, and subscribe to help spread the word!

A daughter of Focus on the Family speaks out: an interview with Amber Cantorna-Wylde

D.L. Mayfield: Today I am talking to Amber Cantorna-Wylde, who is the author of Out of Focus, My Story of Sexuality, Shame, and Toxic Evangelicalism. Amber has a really impactful story that will resonate with a lot of people here. Amber can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Amber Cantorna-Wylde: Let's see. I work primarily in the social justice field, largely because of my upbringing and my background, which I'm sure we'll get into today. I've done social justice advocacy for about eight and a half years, and it’s my passion to help people heal from religious trauma—especially queer people that are coming out of conservative evangelical spaces—and help them love who they are and embrace who they are.

I do a lot of advocacy work. I do a lot of community healing work, where we bring people together and help them find belonging in community. And I am also a creative—so whatever space I can find to cultivate community and healing and aliveness in people is what I thrive on doing. It’s a lot of loving ourselves and healing from what we've been raised in or taught to believe that has done us harm and learning to reprogram those things.

D.L. Mayfield: Do you want to tell us a little bit about your childhood background and who your dad is? Because I think that's going to be very interesting to people for this discussion.

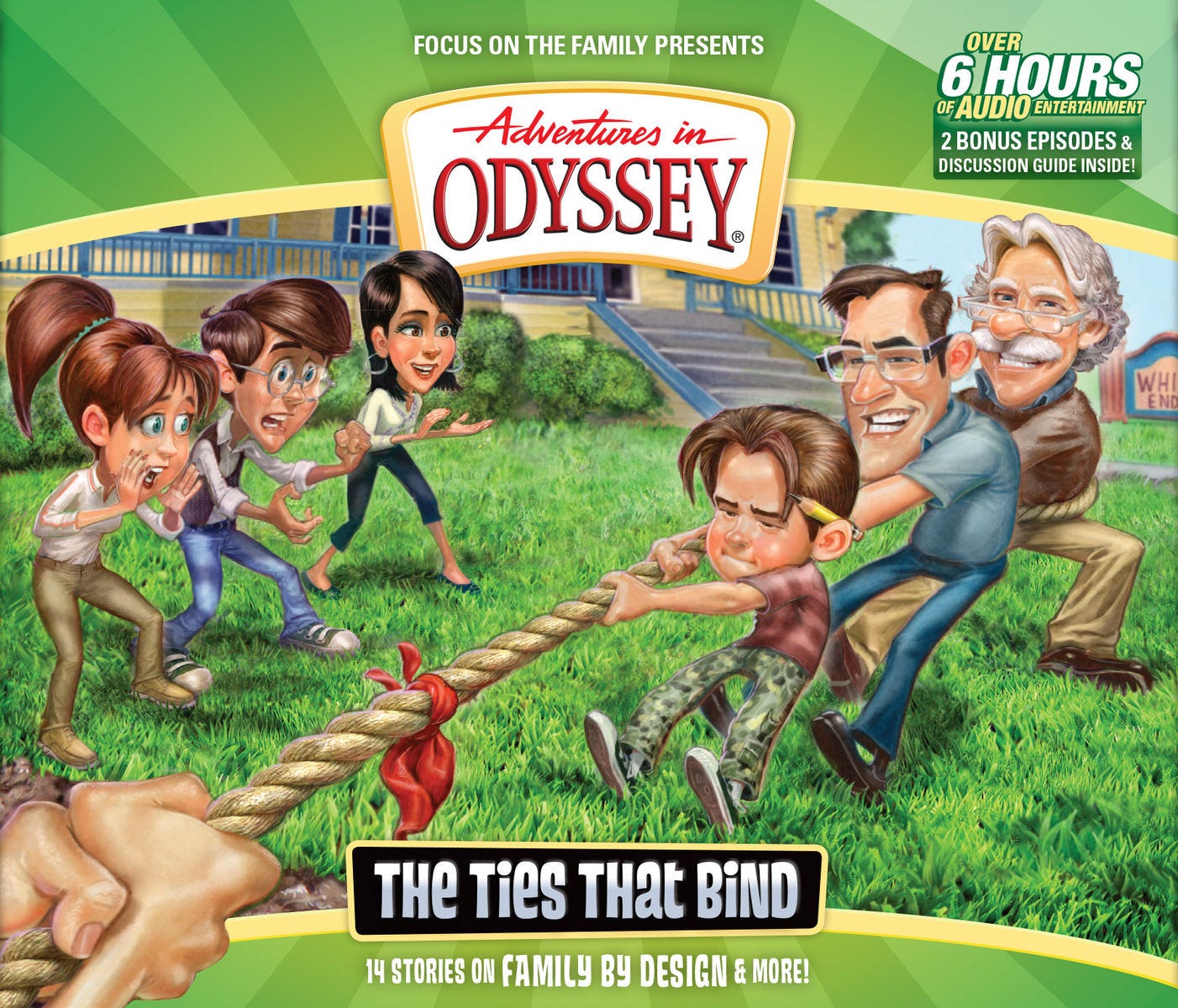

Amber Cantorna-Wylde: Yeah, it’s a little pivotal for this conversation. So I grew up in the heart of Focus on the Family (a conservative non-profit started by Dr. James Dobson). And my dad is Dave Arnold, the executive producer of Adventures in Odyssey and Radio Theater. My dad started working at Focus on the Family when I was three years old. We actually moved from Montana down to the LA area when Focus was still based in Southern California.

And then when they transplanted to Colorado Springs in 1991, my family transplanted with them. And so, it has been an integral part of our family from the very beginning, really. And my dad is still employed there to this day, so it has been hugely impactful in my life as a queer person who came out around 27 years old.

And then my coming out was, of course, a huge breach in our family.It ended up tearing us apart, and I have been estranged from them ever since. That is kind of like the super nutshell version of something that I think a lot of us can relate to on different levels in a very painful way. But I've then tried to use that story as a voice to help other people feel less alone in their own experience of a very similar upbringing. Because I believe that your dad doesn't have to work at Focus for you to be very strongly influenced by Dobson and by Adventures in Odyssey and these characters and these ideas that are being taught from Focus on the Family.

D.L. I think the public work that you do is so impactful because this is something more and more people are starting to talk about—the long term impacts of being raised in sort of a religious authoritarian, or as you call it, toxic evangelicalism. There is this question of where are the kids of these people? People ask me a lot: what about Dr. Dobson's kids? Have they rebelled? And I'm sure you know this, but they have not. They fall within the party lines, and they seem to both make their financial livings off of towing the party line.

And so you are maybe one of the most high profile people who has come out with the negative impacts of this way of raising children with your dad being in charge of Adventures in Odyssey. And for those who don't know, Adventures in Odyssey is a children's radio program that Focus on the Family started which was an integral part of their “ministry” to kids and ministries to families.

Adventures in Odyssey was ostensibly giving kids a safe program to listen to when in reality a lot of it was very propaganda-y, which is similar to most of the materials put out for evangelicals in general. Now, when I come for conservative patriarchal evangelical culture everyone tells me: don't touch Adventures in Odyssey. That's like the one good thing I remember from my childhood.

Because they loved this show as kids! Do people talk to you about this special emotional connection?

Amber I've gotten some of that, yeah, where they still have fond memories of it, right? Where they still look back on it with nostalgia and positivity. And so I think there is that. And I think I held that to a degree myself for quite a while.

As I first told my story when I came out and wrote my first book, I never named my dad. And that was intentional because he was still working there, and I was fairly newly out as gay. I thought there was still hope of reconciliation. I thought well, he's making this program for kids, right? So it's harmless.

And then as I have gotten further into my own journey, as I've deconstructed more, as I've delved more into so many of these topics, my perspective has changed. As I was writing out of Out of Focus, I had this kind of moment where a light bulb came on. It was like, okay. This is not harmless. This is calculated. It is intentional. The way that they are programming these messages into kids from infancy and teaching them exactly how to be and how to behave and how to believe, so that they can continue the exact same belief system moving forward with the next generation, is intentional.

D.L. The word “focus” is interesting because I think that can help us understand how narrow of a role we were all supposed to be playing in these homes. And these narrow roles were being legitimized through every avenue, including kids media, including Adventures in Odyssey. So I wondered, for you, what were some of the pressures that you experienced being the child of one of the main Focus on the Family people?

Amber Well, I think there was a lot of pressure to uphold that family name. To uphold the reputation of my dad, of Focus on the Family, of Adventures in Odyssey, as the daughter of, really the creator of this whole world, there was a lot of pressure that came with that. Pressure to perform, pressure to appear happy, pressure to appear perfect and like our family had it all together.

And I don't think I felt that so much in my elementary years, because I was kind of enamored with the whole thing. But as I got a little bit older into tweens and a young teenager, I started feeling that pressure a lot more from my friends, and certainly feeling it from my family and my parents.

And even from my mom, we were homeschooled, of course, and seen as this leader among the homeschool movement. And so there was pressure from both sides of my parents, to represent them well. And that meant that often my mom would say, well, we need to go into whatever this was, this situation, this meeting, this gathering, whatever, with the idea that we're going to “be a blessing to them.”

And what that really meant was just be on your best behavior. And, what I think I learned as I got older, that it also meant to suppress your own desires, suppress your own needs, and put yourself last at every cost. And that has come with a lot of sticky things to unravel as an adult, right? I'm approaching 40 this year and I’m catching myself trying to recognize my own needs as a human being, when it's so deeply ingrained in me to put myself last after everything and everyone else. Or feeling like my needs are never met, but also knowing I don't know how to advocate for my needs or to ask for what I want.

And that has been something I've had to really focus on and really work through because it was so deeply ingrained in me to deny myself at every cost for the sake of other people.

D.L.: For the sake of your family, right? My own story is that I didn't come out as non-binary till I was 38 because of exactly this kind of thing. You don't even think about yourself. You're not really supposed to think about any of that, you just need to conform to the role that you have in the family. There's just so much pressure to prove that our parents are right, that their ideology is right, their way of raising kids works, that does create these great, healthy, happy families. When in reality, that's not really what is happening. All of us have this different experience of when the pressure got too much but we're still unpacking that in so many ways, so I just really resonate with the fact that we can be in our 30s and 40s just now being like wow the pressure to conform is so much.

I'm curious how much you see rigid gender roles being a part of this equation because that was a huge part of my upbringing.

Amber : Well I was curated from very young to be one kind of woman, right? My mom had an entire girls group that met routinely and a lot of it was around tea parties and homemaking and learning to quilt or bake bread. They would take these ideas from the Proverbs 31 woman and break it down into the traits we were supposed to acquire to be a homemaker, to be a wife that submitted to her husband, to be a mother of children. And when it came to higher education, I remember my mom saying, well, what's the point in going to school and obtaining all this debt if you're just going to get married and have babies?

D.L. : Yeah, my parents never told me to go to college.

Amber: So I've got an associate's degree, but it was essentially trade school. There was not a push for higher education for women because I was expected to essentially be a pastor's wife and then have children and raise a family. And that was kind of all that was out there for me, so I think it very much impacted my upbringing and the way that I viewed myself.

D.L.: One of the things I really appreciate it about your book is that you talk about all this stuff from such a personal lens but you also bring in sort of the systematic and the historical perspective and you mention in your book about the white supremacist roots of Focus on the Family including the gender roles in all this.

Do you want to talk about that just a little bit?

Amber: It kind of goes back to really this whole idea of these culture warriors, right? So if we go back to the beginning and talk about Paul Poponoe—he was an atheist eugenicist who fought for the forced sterilization of women and successfully so. And most people don't know that he ended up being a mentor to James Dobson.

So even though a lot of people don't know Popenoe and his legacy, it lives on through Dobson and the history of Focus on the Family very much because James Dobson was a protege of Popenoe. And a lot of this comes from building up these culture warriors.

They wanted the white patriarchal man to succeed, so they would try and suppress women. They would try and suppress other minorities and people with mental health issues and try to get white straight men in power. And so the women would stay home and they would therefore not have an education, and their job was to have as many children as possible. As we see in things like Shiny, Happy People, with the Duggar family, it was, have as many children as possible and raise them up under this same ideology, so that the children then become the next generation of political leaders and voters to influence and continue this same thing going forward.

The scary thing is that it worked, right? So many of us were homeschooled. We were kept out of public school and public education and these things that could have helped us not only function better in the world, but also, be able to really understand ourselves better. If I had done some of those things, I would have been able to understand my own sexuality earlier. I would have been able to come out earlier. I would have been able to accept myself and there are so many things that could have been different. But because of the way that I was raised, so much of that came at such a higher cost and so much later in life, than it could have otherwise.

D.L. You said it so well—this is all very strategic and it really is built on these rigid gender roles. So you have to suppress one group, which is obviously the women. There's also suppression of children in these homes, right? And children are just supposed to be extensions of the white patriarchal framework. This is something I've really struggled with because as a kid, you're biologically designed to believe the best of your caregivers and your parents. And I really believed that my parents were doing the best they could and that we had a really loving family, right? Now I have a different perspective and it's so jarring.

One of the things I appreciated, but I found it heartbreaking about your book is you did mention this cognitive dissonance. Your family would always tell you : Amber, your friends will come and go, but your family will always be there for you. And what I resonated with your story is that you believed that right up until they proved you wrong because that actually wasn't true at all.

Amber: Right. I remember from a very young age that my mom would tell me that. And so you do trust that, right? Because those are your caregivers. And I did believe that they would always be there for me. Until they weren't. And that of course happened primarily with my coming out.

And when I came out, of course I knew it was a huge risk because of my upbringing. I knew it wasn't going to go well. I knew that it had the potential to be catastrophic, but I didn't really expect it to be that extreme as some of the other horror stories I'd heard. And I think I just wasn't sure where on the spectrum of reactions my family was going to fall.

I think deep down I knew that it could potentially cost me everything, but I wasn't prepared for the fact that it actually would. When I finally got the words out to them they ended up basically interrogating me and comparing me to murderers and pedophiles and telling me I was so selfish to be doing this and how dare I not think of the rest of the family and how this would impact them. Which of course was all I had thought about for months leading up to it! About how this could impact the family and never be the same.

But when you're forced with a decision to be authentic to yourself or suppress who you are and you are facing the mental health ramifications of that, it doesn't really become a choice anymore. And so I chose to come out and move forward with that, but it did end up costing me everything. They took away my keys to their house. It was obviously a very sudden breach and break in our relationship, but we had this awkward period of about a year and a half where we kind of tried to maintain some semblance of a relationship and it was painful. It was not working. It was traumatizing. It was awful. And about a year and a half into it, my dad just kind of drew this line in the sand and was like, this is it. And we haven't spoken since. So I've been out for over 12 years and we haven't had contact in really over a decade.

D.L.: I think your story is such a heartbreaking example of how you would have kept hurting yourself to be in relationship with them, because again, that's what children are biologically designed to do. We will suppress our own needs and desires to get the love, care and attention we deserve from our caregivers. And that doesn't stop in adulthood. This is similar to my own story of how I will hurt myself in order to maintain a relationship.

Amber: Well, and I think that we have been trained to do that, but I don't think that that's healthy.

D.L.: Oh no, absolutely not healthy.

Amber: I advocate now for extreme self care and boundaries because it's so detrimental to your own mental health to constantly suppress who you are in order to please others. That comes at a great cost.

And sometimes having to create that distance, for the sake of your own mental and physical wellbeing is what is necessary. That is hard and it’s heartbreaking, but it is what you have to do to keep yourself healthy and safe. The mental health aspect of this is huge and when you're self harming or you're engaging in risky behaviors or you are hating yourself to the point of suicide, that's not okay.

You need to care for yourself and you need to put boundaries around that to keep yourself safe and healthy. This looks different for every person and every relationship because our stories are all different, and being estranged is very difficult and challenging. It's also very difficult and challenging to remain engaged in a relationship with your parents where you're trying to toe that line, but they're constantly misgendering you, or they're constantly ignoring the fact that you have a partner or all those kind of things. Those are equally challenging things and everybody handles it a little bit differently.

But I encourage people to really prioritize self care and boundaries because you're worth it and you're worthy of that love and belonging.

D.L.: Thank you so much, Amber. That's such a beautiful message.

Let’s go back to these rigid roles assigned to us as children of parents who were all in on this evangelical ideology. The hard part is even when you're an adult your parents still view you as needing to be in this very specific role. And that's something that some people just have to move on from because your parents are never going to change that perspective.

Amber: Yeah.

D.L.: You know, that's unfortunately been my story. That's been a lot of people's story. I am kind of curious because there's a part of your story in your book that really stood out to me, which is after you came out to your dad, he worked very hard on this special Adventures in Odyssey series called The Ties That Bind1. My partner Krispin and I reviewed that series because we found it so deeply upsetting and problematic. And we did this I think four years ago, and it originally came out in 2014.

Amber: Yep.

D.L. Mayfield: You wrote about this series in your book. And I was like, Oh my gosh, I need to talk to Amber about this. So do you want to explain a little bit the background behind this series called The Ties that Bind?

Amber: Yeah, so they actually had done an adult version called The Family Project that was also a 12 week study for adults on what the role of marriage and family should look like. And of course, to them, that means, straight hetero marriage and one type of family. So it's a study that would go through with different questions and like a guide and you could do it in a group or whatever.

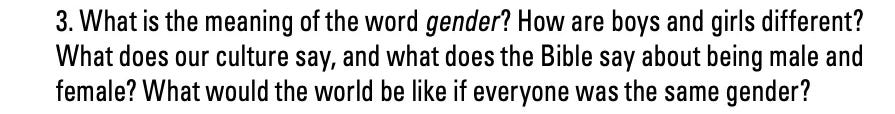

Well then the Ties That Bind was basically the children's version of that and it mirrored the same content, but on the level of a child. And it also came with questions and things that they could discuss. And of course it's very much angled from the perspective that they want kids to understand and come away with that there is only one kind of family and or one kind of acceptable family in the eyes of God.

And so they created this 12 week series that could be done alongside the family project. And so it was, yeah, I think it's very problematic. It's very harmful on a myriad of levels to indoctrinate kids so young rather than teaching them the beauty of diversity in all kinds of families and relationships.

(“God’s design for families” is code for heteronormative marriages where the wife never divorces the husband)

D.L.: Yeah, and not only is it about how there's just one rigid way to be a person and to have a family, the whole series is about how in the town of Odyssey a liberal is trying to put on a tolerance parade.

Amber: AKA a pride parade.

D.L. : Yeah. And so the whole thing is teaching kids why tolerance in general is so bad. What’s interesting is that they don't mention the words like homosexuality. They use these other words like tolerance and activists and all this stuff to teach these little kids that tolerance is not okay. And that we actually need to fight back against tolerance with everything we have. It ends with the town not doing the tolerance parade and everybody's happy and I just thought oh my word . . . and in your book you talk about your dad producing that series right after you came out to him.

(Below are various excerpts from the discussion questions at the end of certain episodes of The Ties That Bind)

Amber: Yeah. It was like two years after I came out. So it's shocking to me. On so many levels. Yeah. It's just deeply disturbing.

D.L.: And here you are out here doing tolerance work.

Amber: Doing the work of tolerance.

D.L.: Mr. Whitaker would be so angry with you.

Amber: Right?

D.L. Mayfield: One thing in that series that stood out to me is that kids who grew up listening to Adventures in Odyssey love the character of Mr. Whittaker in the series. Now, I think Mr. Whittaker is a huge creep, and in The Ties That Bind, he has these very creepy moments of explaining God's design for sexuality to children, right? And I'm like, there is something just so weird about Adventures in Odyssey in general. It is predicated on this idea that a Christian man, an older man, has an ice cream shop for children where he teaches them—with their parents full knowledge—about God.

Everything Focus on the Family puts out for children is geared towards this idea that you should seek out white patriarchal Christian men for guidance and listen to them and everything they do is correct. Everything they do is godly and you have to obey them immediately because they're listening to god. And that creates a recipe for abuse, right, especially if you're not teaching kids about consent, if you're not teaching kids about autonomy, if you are not teaching about agency. Which is very much not taught in these circles, right?

So this is my little diatribe against Mr. Whitaker and Odyssey as being 100 percent a part of the problem here.

Amber: Well, I think that goes really across all of evangelicalism because you are taught to just trust whoever is put in authority over you and not question them at all. And so you're spoon fed this theology and just supposed to go and accept it. And to question anything is bad and to wonder or to seek out other opinions is highly frowned upon.

And that's how they get you, right? That's how they keep you in that very narrow minded way of thinking is by getting you to believe that this is the one person that has the authority to speak on God's behalf and that you have to listen to all that they say. And that is very dangerous.

I mean, I remember how freeing it felt to me when I was starting to question my own sexuality and I went to a church for the first time that allowed space for questioning and for wonder and for curiosity. And that was both terrifying and freeing to me because I had never experienced that before.

Everything in my childhood was so black and white, so right or wrong and so certain that it was so based on certainty, that it was, it is, both terrifying and frightening to break away from that.

D.L.: And I think there's lip service to this idea of certainty in these homes, but a lot of that was just utilized to disconnect us from our own authority, and our own sense of who we were. You were supposed to always defer to the Mr. Whittaker's, right? That's the message that Adventures in Odyssey gives over and over again. You listen to Mr. Whittaker and you don't trust yourself.

Amber: You don't trust yourself. That's the kicker.

D.L. : And that's what makes it so insidious!

Now you mentioned in your book some of the long term impacts that can happen when you have to suppress parts of yourself to survive. Now, I don't know if you want to talk about this, but for me growing up in a home that was really into Dobson methods, suppressing emotions was integral to the discipline process that my parents used with us and that Dobson himself taught. Was that true for you as well?

Amber: I think so. Yeah. I mean, there wasn't a very broad range of emotions in our home. You were pretty much expected to be happy all the time. There wasn't a lot of room for sadness or disappointment or anger or any of those other emotions. And if you felt those things momentarily, they very quickly tried to get you back to a place of happiness and with cliches like, well, you just need to pray harder or you just need to trust God more and everything will be okay and it will all work out for the good and like those kind of things.

And it didn't actually make you feel better. It just made you suppress what you were feeling and hide it deep down, because being seen for what you were actually feeling wasn't acceptable.

D.L.: It wasn't acceptable and it's hard for me to know like how common is this across American culture, like how many kids had parents who couldn't deal with the full range of childhood emotions, but I'm the parent of two kids and I'm not raising my kids that way and it is just so wild to be like—human beings have a lot of emotions and you can't suppress them — they will come out in one way or another.

I often think, wow, there's just so many ways to exploit people who get very good at suppressing certain emotions. How have you learned to feel all your feelings that you maybe weren't allowed to feel in childhood?

Amber: I think it's taken practice and time to really allow myself to explore some of those and to even become comfortable with them because they're so foreign that learning how to become comfortable with them has been a process in itself. And I think that's something that we're going to continue to learn and to unpack as we continue to grow, right?

When you've suppressed emotions all your life, you can't just flip a switch and suddenly feel them all. It's a process of learning how to explore them in a healthy way. And be able to really feel all those things and allow yourself to experience disappointment or sadness or anger and not feel scared or threatened by it.

It's a process and I think it's one that you just continually lean into and try to grow and learn from.

D.L.: In your book you said, “Closeting emotions as a child was what equipped me to closet my sexuality as I got older.” Which really stood out to me, about how learning how to disassociate even from our emotions can lead to us disassociating from some very core parts of who we are.

Amber: Well, I think you're absolutely right.You learn to separate these parts of yourself, and suppress or dissociate. I think that's a fair word. And therefore you dissociate from not only your emotions, but your needs, right? Because not only was sexuality very taboo, but sex itself was very taboo.

And so you learn to dissociate from even your needs as a human being for sex or for intimacy or for love or relationship. And so it's this wicked storm of suppressing emotions, denying who you are, suppressing your feelings, your sexuality, that it can become this lethal storm for many. We are now seeing the massive amount of mental health and suicide rates among people who come from these kind of backgrounds.

D.L.: I know not everybody listening to this or reading this interview identifies as queer or anywhere on that spectrum, but I am curious how you have discovered, how queer communities help folks who have learned to suppress a lot of their life?

Amber: I think queer people are really good at being authentic because they've had to fight so hard to be. And I think that's one of my favorite things about the queer community and the people that I have met on the other side of deconstruction, those kinds of post evangelicals, those ex-evangelicals, those who have deconstructed.

Prior to coming out, I always felt like I lived in this Barbie doll world where everybody just plastered on this happy face all the time and nobody was real with one another. And coming to the other side of that, I feel like people are so raw and authentic and real with each other. And it's such a gift to be able to just hold space and be honest. That's something that I think I craved and longed for all my life that I couldn't ever find until I got on the other side of deconstruction and coming out. And I think that's one of the biggest gifts that I have found with the queer community because you don't just arrive there, right? You have to go through some real shit to get to the other side and to be able to be in that space. So I think the authenticity that we as queer people bring to the table is a real gift. And it's been a gift to me.

D.L.: I see the queer community and I'm like, wow, there's a lot of creativity. There's a lot of joy. There's a lot of playfulness. It's not all just these sad stories, but the sad stories do happen.

And I feel like you're one of those stories that it's just so heartbreaking to see how your family has responded to you. And I see the way that you have chosen to respond to that heartbreak is by reaching out and trying to make the world safer for other people.

The amount of work you've had to do to not only process your childhood, but then to decide, I actually want to make the world better for other people. I just can't say how meaningful that is to me. And I've seen so many other queer people do that work. I know that they are reaching from the very core of themselves to help other people because they didn't actually get unconditional love or support from their caregivers, yet they are offering that to others.

So I see you in that community of people. I just want to thank you so much, Amber, for that. And I know you've talked a little bit about mental health and physical impacts. I know in our STRONGWILLED community, a lot of people are dealing with long term health and mental health implications from being raised in religious authoritarian homes.

Amber: I think there's a strong connection between chronic illness and identity suppression.

D.L.: So do I.

Amber: I mean, I have lived with chronic illness now for 10 years and I've been out as a queer person for 12. So the timing there isn't very far off. And, I have met a number of people that come from evangelical backgrounds who have come out as queer that also deal with severe chronic illness on a variety of levels.

And I think that when you've been taught to suppress who you are, or you've been taught to hate who you are, that does not go unresolved or unnoticed in your body. And that comes out in hideous ways. I think that's partly why I advocate so strongly for going back to what we were talking about earlier with self care and boundaries, because your mental and physical health is the most important thing. It is not your family's reputation. It is not their family name or upholding those things. Your health is the most important thing. And once you have lost that to a degree, like you can't necessarily get it back. I mean, I hope to someday be in remission with mine, but I am not there yet and it will never be what it once was or could have been.

Your mental and physical health is the most important thing. It is not your family's reputation. It is not their family name or upholding those things. Your health is the most important thing. And once you have lost that to a degree, like you can't necessarily get it back.

So I think that protecting it as early as you possibly can and fighting for that as soon as you get the chance, and doing whatever you can to help reduce those risks, is a gift to yourself that you absolutely deserve. The long term impacts are definitely there for sure.

D.L.: I think both the repression of gender or sexuality, but also just of emotions in general has a very negative impact on your nervous system and on other parts of your body. So even if people don't identify as queer in any way, If you had to suppress emotions as a child, just learning to be in touch with emotions, learning to be in touch with your body can help with some of this, but it doesn't fix it all because we're suddenly in touch with ourselves a little bit better.

Amber: I recommend somatic practices or yoga or meditation, there's things that can help you get in tune with both your body and your emotions, and it’s a good step in the right direction, I think.

D.L.: I agree. I'm into somatic therapy right now and it is so helpful for me and my own chronic pain and chronic anxiety and depression. And thanks again for mentioning at the end, just going full circle back to your experience with your family of coming out, of being estranged for so many years now. Just that there is a [mental and physical] cost to being in relationship with people that need you to suppress integral parts of you.

Amber: Yep. Yeah.

D.L.: We, of course, can never tell people what to do, and everybody gets to make their own decisions, but I think it's just important to keep saying that.

Okay, my last question is kind of an odd one. Did you ever meet James Dobson?

Amber: I actually have a picture with James Dobson when I'm three years old. I actually put it in the book. And it's so funny because I have this disgusted look on my face. So you can tell that we didn't like each other from the very beginning, you know, we never hit it off from the start.

D.L.: Wow, he probably thought you were strong willed or something, right?

Amber: Yeah. Needing discipline.

D.L.: Well, Amber, thanks so much for coming on here to talk to me. Where can people find you? Where can they find your work? And if they want you to come do some public speaking or consulting work, where can they find you?

Amber: My website is probably the best place for all of that. It's ambercantornawylde.com and it's kind of the house for all of my things. It gives you a link to some speaking stuff. You can certainly reach out to me there if you want me to do any kind of speaking or consulting. I lead a small online community called the Unashamed Love Collective and all that information is there.

You can find me on Instagram and Facebook at Amber Cantorna-Wylde.

D.L.: And everyone, I encourage you to check out Amber's book, Out of Focus. It's very readable. There's some really intense things that happened and even though it was your very personal story, I was like, whoa, this also happened to me.

So it was really helpful for processing. Your vulnerability, and also your sense of humor, your creativity, all that also shines through. So, people don't have to be scared of reading it—I don't think it's going to re-traumatize anybody to read it,

Thanks so much for writing your book and for doing this public work, even though you are somebody who's living with chronic illness and pain. Thank you for showing up.

Amber: Yeah. Thanks for having me. Great conversation. Appreciate you.

If you appreciate our content, consider supporting STRONGWILLED so we can continue to interview and pay our guest contributors like Amber. Thank you so much for reading, sharing, liking, and supporting this work!

You can listen to the episodes where we review the Ties that Bind beginning in 2019 on spotify or wherever you get your (old) podcasts. Be warned, we were both still very Christian when we were recording these episodes!

I love Amber, I love her book (it’s so well-written and engaging), and I loved this convo. Thank you both!! I think of Amber a lot while I’m making JimDob art. 😁 If you ever need some lighthearted content to break up the hard stuff here at Strongwilled, I’d be happy to share about my art and how healing it is but also how much I enjoy mocking him. 😆

I suddenly partially regret reading the audiobook of Out of Focus for missing out on that pic with Jimmy Dob. 😂 Just finished Amber’s book for Pride month series/book discussion at my church so I loved to wake up to this collab!! I didn’t grow up with AIO the way my spouse did (had like 4 episodes and listened to it on tape or disc whenever on car rides with friends from my church), and it messed up figuring out their gender-fluid identity or having words besides thinking “sometimes too much like a girl” for a looooong time! On a phone call with my in-laws last night, they apparently found a treasure trove of AIO cleaning out and asked if we wanted them. I gestured discs since we don’t have a tape player anymore and wrote down “cult curiosity” on a napkin to get my spouse to ask for them (so we can dissect them on this side of deconstruction/deconversion).